Teaching Approaches/Inquiry: Difference between revisions

SimonKnight (talk | contribs) |

SimonKnight (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 171: | Line 171: | ||

=Inquiry and Mathematics Teaching= | =Inquiry and Mathematics Teaching= | ||

{{adaptedfrom|Fibonacci Project|Reference|Ideas of how to solve particular types of mathematical problems, e.g. involving fractions or negative numbers, are built up through bringing together experiences of tackling a range of related problems. In some cases, a conceptual step may also force to deconstruct, then to reconstruct a new and more encompassing idea. Such progression of ideas is only understood if they make sense to the learner because they are products of their own thinking. This view of learning argues for students to have experiences which enable them to work out for themselves how to make sense of different aspects of the world. First-hand experiences are important, particularly for younger children, but all learners need to develop the skills used in testing ideas – questioning, predicting, observing, interpreting, communicating and reflecting. | |||

As is the case in natural science, inquiry-based mathematics education (IBME) refers to an education which does not present mathematics to pupils and students as a ready-built structure to appropriate. Rather it offers them the opportunity to experience | |||

* how mathematical knowledge is developed through personal and collective attempts at answering questions emerging in a diversity of fields, from observation of nature as well as the mathematics field itself, | |||

* how mathematical concepts and structures can emerge from the organization of the resulting constructions, and then be exploited for answering new and challenging problems. | |||

It is expected that the inquiry-based approach will improve students’ mathematical understanding which will result in their mathematical knowledge becoming more robust and functional in a diversity of contexts beyond that of the usual school tasks. It will help students develop mathematical and scientific curiosity and creativity as well as their potential for critical reflection, reasoning and analysis, and their autonomy as learners. It will also help them develop a more accurate vision of mathematics as a human enterprise, consider mathematics as a fundamental component of our cultural heritage, and appreciate the crucial role it plays in the development of our societies. | |||

If it is to be more than a slogan, IBME requires the development of appropriate educational strategies. These strategies must acknowledge the experimental dimension of mathematics and the new opportunities that digital technologies offer for supporting it. | |||

The history of mathematics shows that such an experimental dimension is not new, but in the last decades technological evolution has dramatically changed its means, economy, and also made it more visible and shared by the mathematical community. Compared with experimental practices in natural sciences, one must however be aware that the terrain of experience for mathematics learning is not limited to what is usually called the “real world”. | |||

As they become familiar, mathematical objects also become the terrain for mathematics experimentation. Numbers, for instance, have been used for centuries and are still an incredible context for mathematics experiments, and the same can be said of geometrical forms. Patterns play a great role in mathematics, whether they are suggested by the natural world or fully imagined by the mathematician’s mind. Playing with patterns is a stimulating mathematical activity in the context of inquiry, even for elementary school children. Digital technologies also offer new and powerful tools for supporting investigation and experimentation in these mathematical domains. | |||

IBME must, therefore, not just rely on situations and questions arising from real world phenomena, even if the consideration of these is of course very important, but use the diversity of contexts which can nurture investigative practices in mathematics. | |||

Mathematics has a cumulative dimension to a greater extent than the natural sciences. Mathematical tools developed for solving particular problems need to build on each other to become methods and techniques which can be productively used for solving classes of problems, eventually leading to new mathematical ideas and even theories, and new fields of applications. Moreover, connections between domains play a fundamental role in the development of mathematics. Thus it is important in implementing IBME that students do not deal only with isolated problems, however challenging they may be, since this may not enable them to develop the over-arching (or more generally applicable) mathematical concepts. | |||

Selecting appropriate questions and tasks for promoting IBME thus requires the consideration of their potential according to a diversity of criteria, and the building of a coherent organization and progression among these, having in mind the characteristics of mathematics as a scientific discipline and the ambition of such education of emphasizing the interaction between mathematics and other scientific disciplines, between mathematics and the real world. | |||

A further crucial point is that, even when they emerge from real world situations, mathematical ideas are not directly accessible to our physical senses, and are thus worked out through a rich diversity of semiotic systems: standard systems of representation such as graphs, tables, figures, symbolic systems, computer representations, etc., but also gestures and discourse in ordinary language. IBME must be sensitive to this semiotic dimension of mathematical learning and to the progressive development of associated competences, without forgetting the evolution in semiotic potential and needs resulting from technological advances. | |||

Modern technological tools have an impact on inquiry-based education through the immediate access given to a huge diversity of information, whatever the topic. This situation means that the “milieux” with which students can interact in investigative practices are potentially much richer than those usually used for developing investigative practices in mathematics. However, the necessity of selection and the critical use of such information create new demands that iBMe must take into account. | |||

=Inquiry and Science Teaching= | =Inquiry and Science Teaching= | ||

Revision as of 13:18, 29 August 2012

Inquiry and Pedagogy

You might want to watch this video on use of collaborative enquiry in classroom tasks www.teachersmedia.co.uk/videos/collaborative-enquiry including a brief overview of the research.

Overview

{{adaptedfrom|Edutech wiki http://edutechwiki.unige.ch/en/Inquiry-based_learning CC licensed|WholePage|"Inquiry learning is not about memorizing facts - it is about formulation questions and finding appropriate resolutions to questions and issues. Inquiry can be a complex undertaking and it therefore requires dedicated instructional design and support to facilitate that students experience the excitement of solving a task or problem on their own. Carefully designed inquiry learning environments can assist students in the process of transforming information and data into useful knowledge" (Computer Supported Inquiry Learning, retrieved 18:31, 28 June 2007 (MEST).

Inquiry-based learning is often described as a cycle or a spiral, which implies formulation of a question, investigation, creation of a solution or an appropriate response, discussion and reflexion in connexion with results (Bishop et al., 2004). IBL is a student-centered and student-lead process. The purpose is to engage the student in, ideally based on their own questions. Learning activities are organized in a cyclic way, independently of the subject. Each question leads to the creation of new ideas and other questions.

This learning process by exploration of the natural or the constructed/social world leads the learner to questions and discoveries in the seeking of new understandings. With this pedagogic strategy, children learn science by doing it (Aubé & David,2003). The main goal is conceptual change.

IBL is socio-constructivist (based broadly on Vygotskian ideas), emphasising the importance of within which the student finds resources, uses tools and resources produced by inquiry partners. Thus, the student make progress by work-sharing, and building on everyone's work.

Models

There are many models described in the literature. We shall present as an example the cyclic inquiry model presented on the inquiry page sponsored by "Chip" Bruce et. al of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC).

Cyclic Inquiry model

The purpose of the UIUC inquiry model is the creation of new ideas and concepts, and their spreading in the classroom.

The Inquiry cycle is a process which engages students to ask and answer questions on the basis of collected information and which should lead to the creation of new ideas and concepts. The activity often finishes by the creation of a document which tries to answer the initial questions.

The cycle of inquiry has 5 global steps: Ask, Investigate, Create, Discuss and Reflect. We will give an example for each step using the "rainbow" example from Villavicencio (2000) who works on light and colors every year with 4 or 5 years old children.

from: [The Inquiry Page]

During the preparation of the activity, teachers have to think about how many cycles to do, how to end the activity (at the Ask step): when/how to rephrase questions or answer them and express followup questions.

Ask

Ask begins with student's curiosity about the world, ideally with their own questions. The teacher can stimulate the curiosity of the student by giving an introduction talk related to concepts that have to be acquired. It's important that student formulate their own questions because they then can explicitly express concepts related to the learning subject.

This step focuses on a problem or a question that students begin to define. These questions are redefined again and again during the cycle. Step's borders are blurred: a step is never completely left when the student begins the next one.

Rainbow Scenario : The teacher gives some mirrors to the children, so they can play with the sunlight which are passing trough the classroom's windows. With these manipulations, students can then formulate some questions about light and colors.

Investigate

Ask naturally leads to Investigate which should exploit initial curiosity and lead to seek and create information. Students or groups of students collect information, study, collect and exploit resources, experiment, look, interview, draw,... They already can redefine "the question", make it clearer or take another direction. Investigate is a self-motivating process totally owned by the active student.

Rainbow Scenario : Once questions have been asked, the teacher gives to the children some prisms which allow to bend the light and a Round Light Source (RLS), a big cylindrical lamp with four colored windows through a light ray can pass. Then the children can mix the colors and see the result of their mixed ray light on a screen. They begin to collect information...

Create

Collected information begins to merge. Student start making links. Here, ability to synthesize meaning is the spark which creates new knowledge. Student may generate new thoughts, ideas and theories that are not directly inspired by their own experience. They write them down in some kind of report.

Rainbow Scenario : Some links are created from collected information and children understand that rainbows have to be created by this kind of phenomenon.

Discuss

At this point, students share their ideas with each other, and ask others about their own experiences and investigations. Such knowledge-sharing is a community process of construction and they begin to understand the meaning of their investigation. Comparing notes, discussing conclusions and sharing experiences are some examples of this active process.

Rainbow Scenario : children often and spontaneously sit around the RLS. They discuss and share their newly acquired knowledge with the purpose to understand the mix of colors. Then, they are invited to share their findings with the rest of the class, while the teacher takes notes on the blackboard.

Reflect

This step consists in taking time to look back. Think again about the initial question, the path taken, and the actual conclusions. Student look back and maybe take some new decisions: "Has a solution been found ?", "did new questions appear?", "What could they ask now ?",...

Rainbow Scenario : teacher and students take time to look back at the concepts encountered during the earlier steps of the activity. They try to synthesize and to engage further planning on the basis of their recently acquired concepts.

Continuation

Once the first cycle is over, students are back the Ask step and they can choose between two options:

- Ask: a new cycle starts, fed by the new questions or reformulations of earlier ones. The teacher can create groups to stimulate discussions and interest.

- Answer: the activity is ending. The teacher has to finish it by broadening: The initial questions with their responses, the reformulated ones, new ones that appeared during the activity. Making a synthesis is always a better solution, even if this step is not the purpose of an entire cycle.

Rainbow Scenario : the teacher sets students free to repeat their experiments or to try different things. Some students try to replicate what their friends have done, others do the same things with or without variants. A new cycle begins.

The advantage of this model is that it can be applied with lots of student types and lots of matters. Moreover, the teacher can design the scenario by focusing on a part of the cycle or another. He can use one, few or more cycle. Most often, a single cycle (formal or not) is not enough and because of that, this model is often drawn in a spiral shape.

Other models

The model we presented above represents probably the dominant view of inquiry learning. It combines more radical open-ended socio-constructivist principles with a model of guidance. As opposed to Learning by design, most inquiry-based models advocate opportunistic (i.e. adaptive) planning by the teacher. Other models include

- knowledge-building community model (a much more open ended version, geared toward "design mode")

- Scaffolded knowledge integration

- Learning by design

- Computer simulation (The "Dutch school")

Examples cases

- Cyber 4OS Wiki de l'IBL en cours Lombard, F. (2007). Empowering next generation learners : Wiki supported Inquiry Based Learning ? (Paper) presented at the European practise based and practitioner conference on learning and instruction Maastricht 14-16 November 2007.

- P. S. Blackawton et al. [Blackawton bees, December 22, 2010, doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2010.1056.

- See also: 8-Year-Olds Publish Scientific Bee Study.

Links

- inquiry page

- Computer Supported Inquiry Learning Kaleidoscope and EARLI Special Interest Group (SIG)

Bibliography

- Ackermann, E.K. (2004). Constructing Knowledge and Transforming The World. In Tokoro, M. & Steels, L. (2004). A Learning Zone Of One's Own. pp17-35. IOS Press

- Aubé, M. & David, R. (2003). Le programme d’adoption du monde de Darwin : une exploitation concrète des TIC selon une approche socio-constructiviste. In Taurisson, A. & Senteni, A.(2003). Pédagogie.net : L’essor des communautés d’apprentissage. pp 49-72.

- Barab, S.A., Hay, K.E., Barnett, M., & Keating, T. (2000). Virtual Solar System Project: Building understanding through model building. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37, 719–756. Abstract

- Bishop, A.P.,Bertram, B.C.,Lunsford, K.J. & al. (2004). Supporting Community Inquiry with Digital Resources. Journal Of Digital Information, 5 (3).

- Chakroun, M. (2003). Conception et mise en place d'un module pédagogique pour portails communautaires Postnuke. Insat, Tunis. Mémoire de licence non publié.

- De Jong, T. & Van Joolingen, W.R. (1997). Scientific Discovery Learning with Computer Simulations of Conceptual Domains. University of Twente, The Netherland

- de Jong, Ton (2006) Computer Simulations: Technological Advances in Inquiry Learning, Science 28 April 2006 312: 532-533 DOI: 10.1126/science.1127750

- De Jong, T. (2006b). Scaffolds for computer simulation based scientific discovery learning. In J. Elen & R. E. Clark (Eds.), Dealing with complexity in learning environments (pp. 107-128). London: Elsevier Science Publishers.

- Dewey, J. (1938) Logic: The Theory of Inquiry, New York: Holt.

- Duckworth, E. (1986). Inventing Density. Monography by the North Dakota Study Group on Evaluation, Grand Forks, ND, 1986.

Internet : www.exploratorium.edu/IFI/resources/classroom/inventingdensity.html

- Drie, J. van, Boxtel, C. van, & Kanselaar, G. (2003). Supporting historical reasoning in CSCL. In: B. Wasson, S. Ludvigsen, & U. Hoppe (Eds.). Designing for Change in Networked Learning Environments. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Press, pp. 93-103. ISBN 1-4020-1383-3.

- Eick, C.J. & Reed, C.J. (2002). What Makes an Inquiry Oriented Science Teacher? The Influence of Learning Histories on Student Teacher Role Identity and Practice. Science Teacher Education, 86, pp 401-416.

- Gurtner, J-L. (1996). L'apport de Piaget aux études pédagogiques et didactiques. Actes du colloque international Jean Piaget, avril 1996, sous la direction de Ahmed Chabchoub. Publications de l'institut Supérieur de l'Education et de la Formation Continue.

- Hakkarainen, K and Matti Sintonen (2002). The Interrogative Model of Inquiry and Computer- Supported Collaborative Learning, Science and Education, 11 (1), 25-43. (NOTE: we should cite from this one !)

- Hakkarainen, K, (2003). Emergence of Progressive-Inquiry Culture in Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, Science and Education, 6 (2), 199-220.

- Joolingen van, Dr. W.R. and King, S. and Jong de, Prof. dr. T. (1997) The SimQuest authoring system for simulation-based discovery learning. In: B. du Boulay & R. Mizoguchi (Eds.), Artificial intelligence and education: Knowledge and media in learning systems. IOS Press, Amsterdam, pp. 79-86. PDF

- Kasl, E & Yorks, L. (2002). Collaborative Inquiry for Adult Learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 94, summer 2002.

- Keys, C.W. & Bryan, L.A. (2001). Co-Constructing Inquiry-Based Science with Teachers :

Essential Research for Lasting Reform. Journal Of Research in Science Teaching, 38 (6), pp 631-645.

- Lattion, S.(2005). Développement et implémentation d'un module d'apprentissage par investigation (inquiry-based learning) au sein d'une plateforme de type PostNuke. Genève, Suisse. Mémoire de diplôme non-publié. PDF

- Linn, Marcia C. Elizabeth A. Davis & Philip Bell (2004). (Eds.), Internet Environments for Science Education: how information technologies can support the learning of science, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, ISBN 0-8058-4303-5

- Mayer, R. E. (2004), Should there be a three strikes rule against pure discovery? The case for guided methods of instruction. Am. Psych. 59 (14).

- McKenzie, J. (1999). Scaffolding for Success. From Now On, ,The Educationnal Technology Journal, 9(4).

- National Science Foundation, in Foundations: Inquiry: Thoughts, Views, and Strategies for the K-5 Classroom (NSF, Arlington, VA, 2000), vol. 2, pp. 1-5 HTML.

- Nespor, J.(1987). The role of beliefs in the practice of teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 19, pp 317-328.

- Polman, Joseph (2000), Designing Project-based science, Teachers College Press, New York.

- Vermont Elementary Science Project. (1995). Inquiry Based Science: What Does It Look Like? Connect Magazine, March-April 1995, p. 13. published by Synergy Learning.

Internet: http://www.exploratorium.edu/IFI/resources/classroom/inquiry_based.html

- Villavicencio, J. (2000). Inquiry in Kindergarten. Connect Magazine, 13 (4), March/April 2000. Synergy Learning Publication.

- Vosniadou, S., Ioannides, C., Dimitrakopoulou, A. & Papademetriou, E. (2001). Designing learning environments to promote conceptual change in science. Learning and Instruction ,11, pp 381-419.

- Waight Noemi, Fouad Abd-El-Khalick, From scientific practice to high school science classrooms: Transfer of scientific technologies and realizations of authentic inquiry, Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 2011, 48, 1. DOI:10.1002/tea.20393

- Watson, B. & Kopnicek, R. (1990). Teaching for Conceptual Change : confronting Children Experience. Phi Delta Kappan, May 1990, pp 680-684.}}

What Is Enquiry?

One model of enquiry based learning combines the sixteen habits of mind (Costa and Kallick, 2000) and metacognitive skills and knowledge. Habits of Mind (Costa and Kallick, 2000) are persisting, thinking and communicating with clarity and precision, managing impulsivity, gathering data through all senses, listening with understanding and empathy, creating, imagining, innovating ,thinking flexibly, responding with wonderment and awe, thinking about thinking (metacognition), taking responsible risks, striving for accuracy, finding humour, questioning and posing problems, thinking interdependently, applying past knowledge to new situations, remaining open to continuous learning.

Metacognitiveskills and knowledge include; knowledge of self, knowledge of disposition, knowledge of strategies and tools, knowledge of problems and outcomes, and the skills of planning, monitoring and refining.

The enquiry model includes a ‘cycle’ of learning from an initiation stage where pupils are given a stimulus to be developed through. Pupils then refine questions so that they have one main focus they wish to investigate. Subsequent stages involve planning, monitoring, refining, evaluating and presenting.

The enquiry model of learning is also supported by a number of, for example 8Qs, diamond ranking, inference square, odd one out, target board, and mapping.

The framework for enquiry is based on a model of formative self- by the pupils against metacognitive skills and knowledge using the habits of mind (Costa and Kallick, 2000) as a language for learning. Indeed, the aim is that by developing pupils’ awareness of and proficiency in these skills, they will ‘engage in the excitement of learning’ (DfES, 2005) and become better at it. (Adapted from Enquiry Skills in a Virtual World, section WhatIsEnquiry).

A different model of enquiry-based learning encourages students to use exploration, reflection and techniques, sharing of ideas, and high quality. The role of the teacher during the process is to act as a guide who challenges the students to think beyond their current processes by asking divergent questions. The model drew on research into enquiry-based learning that shows that often students experience difficulties in formulating appropriate questions which focus on the intended content. In this context the teacher needs to help them by drawing their attention to the experimental data and facts relevant to their enquiry and by generally facilitating the discussion. (Adapted from The impact of enquiry-based science teaching on students' attitudes and achievement, section WhatIsEnquiry).

What characterises higher-order scientific enquiry skills?

Learners take responsibility for their own learning and, where appropriate, demonstrate a range of the following:

Plan

- recognise that science is based on evidenced theories rather than facts

- justify the methods and strategies that are going to be used in the enquiry

- use concepts such as reliability, accuracy of measuring, validity of data/information when justifying a planned method

- make multiple links between what is already known and/or independent research in order to plan

- take account of any possible problems with their plan in order to refine it

- justify their predictions, which can be quantitative, by using abstract scientific ideas, including linking models, theories and systems

- determine success criteria in complex, abstract tasks

Develop

- communicate effectively, choosing an appropriate medium, selecting only relevant points of interest and taking full account of the audience

- measure systematically with accuracy

- justify any amendments they make to their methodology understand the purposes of, and utilise, a wide range of learning/thinking strategies

- use calculations to demonstrate or explore findings, and in doing so confidently and accurately rearrange equations

- analyse and evaluate findings, looking to see if they present any further issues or modifications to the process they have used

- apply the conventions of reliability and validity to their findings explore any uncertainties or anomalies using scientific reasoning evaluate findings in terms of levels of bias, reliability and validity

- critically evaluate findings in terms of their prior scientific knowledge and understanding

- apply abstract, linked scientific knowledge in a way that demonstrates understanding

Reflect

- evaluate success criteria in complex, abstract tasks

- link the learning to abstract ideas in order to make further predictions

- evaluate the learning/thinking strategies used

- refine learning/thinking strategies for further use

- develop alternative learning/thinking strategies

- critically reflect on their learning and develop their own next steps. (Adapted from Developing Higher Order Scientific Enquiry Skills, section WhatIsEnquiry).

What are the features of quality enquiries?

Learner-centred learning

In order to set appropriate enquiries, it is important to know learners' prior skills, knowledge and understanding. Knowing where learners are in a continuum will enable teachers and learners to better negotiate where learners need to go next and how best to get there; high quality is key to this.

Classroom management

Learners work best when they can share ideas and articulate their thoughts. Establishing effective in the classroom is key to successful learning. Through working in random pairs and small, learners learn from each other, raising their expectations and achievements. Teachers are able to listen in to conversations, and ask leading as in the enquiry 'What's the best way to minimise global warming?', in order to ascertain progress or otherwise. Learners need to agree on, and be frequently reminded of, the basic rules for interaction. They also need to feel that the classroom is a safe and reflective environment in which to take risks with their ideas. (Adapted from Developing Higher Order Scientific Enquiry Skills, section WhatIsGoodEnquiry).

Inquiry and Mathematics Teaching

{{adaptedfrom|Fibonacci Project|Reference|Ideas of how to solve particular types of mathematical problems, e.g. involving fractions or negative numbers, are built up through bringing together experiences of tackling a range of related problems. In some cases, a conceptual step may also force to deconstruct, then to reconstruct a new and more encompassing idea. Such progression of ideas is only understood if they make sense to the learner because they are products of their own thinking. This view of learning argues for students to have experiences which enable them to work out for themselves how to make sense of different aspects of the world. First-hand experiences are important, particularly for younger children, but all learners need to develop the skills used in testing ideas – questioning, predicting, observing, interpreting, communicating and reflecting.

As is the case in natural science, inquiry-based mathematics education (IBME) refers to an education which does not present mathematics to pupils and students as a ready-built structure to appropriate. Rather it offers them the opportunity to experience

- how mathematical knowledge is developed through personal and collective attempts at answering questions emerging in a diversity of fields, from observation of nature as well as the mathematics field itself,

- how mathematical concepts and structures can emerge from the organization of the resulting constructions, and then be exploited for answering new and challenging problems.

It is expected that the inquiry-based approach will improve students’ mathematical understanding which will result in their mathematical knowledge becoming more robust and functional in a diversity of contexts beyond that of the usual school tasks. It will help students develop mathematical and scientific curiosity and creativity as well as their potential for critical reflection, reasoning and analysis, and their autonomy as learners. It will also help them develop a more accurate vision of mathematics as a human enterprise, consider mathematics as a fundamental component of our cultural heritage, and appreciate the crucial role it plays in the development of our societies.

If it is to be more than a slogan, IBME requires the development of appropriate educational strategies. These strategies must acknowledge the experimental dimension of mathematics and the new opportunities that digital technologies offer for supporting it. The history of mathematics shows that such an experimental dimension is not new, but in the last decades technological evolution has dramatically changed its means, economy, and also made it more visible and shared by the mathematical community. Compared with experimental practices in natural sciences, one must however be aware that the terrain of experience for mathematics learning is not limited to what is usually called the “real world”.

As they become familiar, mathematical objects also become the terrain for mathematics experimentation. Numbers, for instance, have been used for centuries and are still an incredible context for mathematics experiments, and the same can be said of geometrical forms. Patterns play a great role in mathematics, whether they are suggested by the natural world or fully imagined by the mathematician’s mind. Playing with patterns is a stimulating mathematical activity in the context of inquiry, even for elementary school children. Digital technologies also offer new and powerful tools for supporting investigation and experimentation in these mathematical domains.

IBME must, therefore, not just rely on situations and questions arising from real world phenomena, even if the consideration of these is of course very important, but use the diversity of contexts which can nurture investigative practices in mathematics.

Mathematics has a cumulative dimension to a greater extent than the natural sciences. Mathematical tools developed for solving particular problems need to build on each other to become methods and techniques which can be productively used for solving classes of problems, eventually leading to new mathematical ideas and even theories, and new fields of applications. Moreover, connections between domains play a fundamental role in the development of mathematics. Thus it is important in implementing IBME that students do not deal only with isolated problems, however challenging they may be, since this may not enable them to develop the over-arching (or more generally applicable) mathematical concepts.

Selecting appropriate questions and tasks for promoting IBME thus requires the consideration of their potential according to a diversity of criteria, and the building of a coherent organization and progression among these, having in mind the characteristics of mathematics as a scientific discipline and the ambition of such education of emphasizing the interaction between mathematics and other scientific disciplines, between mathematics and the real world.

A further crucial point is that, even when they emerge from real world situations, mathematical ideas are not directly accessible to our physical senses, and are thus worked out through a rich diversity of semiotic systems: standard systems of representation such as graphs, tables, figures, symbolic systems, computer representations, etc., but also gestures and discourse in ordinary language. IBME must be sensitive to this semiotic dimension of mathematical learning and to the progressive development of associated competences, without forgetting the evolution in semiotic potential and needs resulting from technological advances.

Modern technological tools have an impact on inquiry-based education through the immediate access given to a huge diversity of information, whatever the topic. This situation means that the “milieux” with which students can interact in investigative practices are potentially much richer than those usually used for developing investigative practices in mathematics. However, the necessity of selection and the critical use of such information create new demands that iBMe must take into account.

Inquiry and Science Teaching

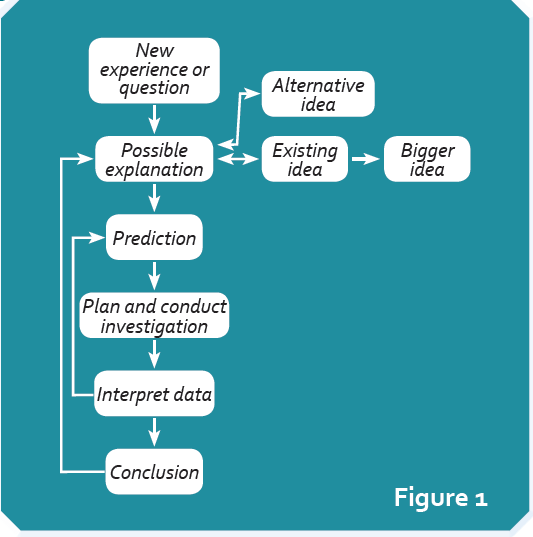

{{adaptedfrom|Fibonacci Project|Reference|The process of inquiry begins by trying to make sense of a phenomenon, or answer a question, about why something behaves in a certain way or takes the form it does. Initial exploration reveals features that recall previous ideas leading to possible explanations There might be several ideas from previous experience that could be relevant and through discussion one of these is chosen as giving the possible explanation or hypothesis to be tried. The test of the hypothesis is whether there is evidence to support a prediction based on it, for only if ideas have predictive power are they valid. To test the prediction new data about the phenomenon or problem are gathered, then analysed and the outcome used as evidence to compare with the predicted result. This is the ‘prediction –> plan and conduct investigation –> interpret data’ sequence in Figure 1. More than one prediction and test is desirable and so this sequence may be repeated several times.

From these results a tentative conclusion can be drawn about the initial idea. If it gives a good explanation then the existing ideas is not only confirmed, but becomes more powerful – ‘bigger’ –because it then explains a wider range of phenomena. Even if it doesn’t ‘work’ and an alternative idea has to be tried (one of the alternative ideas in Figure 1), the experience has helped to refine the idea, so knowing that the existing idea does not fit is also useful. This is the process of building understanding through collecting evidence to test possible explanations and the ideas behind them in a scientific manner, which we describe as learning through scientific inquiry.

The use of ICT to support Inquiry

Information and communication technologies provide today powerful tools for supporting inquiry-based education in mathematics and science. These tools are quite diverse

- specific educational interfaces developed for supporting the collection and analysis of experimental data in a diversity of scientific domains;

- microworlds attached to specific scientific or mathematical domains, as are in mathematics the various software tools for algebra, calculus and geometry;

- simulation tools such as Net-Logo which make possible the exploration the behavior of complex systems, and the identification of regularities often not easily accessible through pure analytic work;

- more general tools such as spreadsheets, statistic software, tools for numeric and symbolic computations, for graphical representations, not necessarily designed for education but converted then into educational tools.

Most of these ICT tools, implemented in hand–held devices or computers, have been present in the educational area for two decades at least. Their potential for supporting experimental practices and inquiry-based learning in science and mathematics has been investigated by educational researchers and attested in experimental settings. However, their influence at large on mathematics and science education has remained quite limited. But the situation is getting better as EU projects (e.g. Intergeo and InnoMathEd) and national projects (e.g. in the Netherlands and Germany) show. In the last decade, Internet technology has substantially moved this educational landscape:

- making many of these technologies accessible online, and leading to new forms of educational objects, such as so-called applets (small interactive software components that can be accessed through an Internet browser);

- giving easy access to a huge amount of information, whatever be the question at stake, and to professional data bases;

- leading to an exponential increase in the number of resources produced both for students and teachers, by individuals, collectives or institutions, and changing the usual patterns of production and dissemination;

- supporting the development of collaborative practices both on the side of students and teachers, and the development of networks.

Dynamic worksheets which are more and more used for supporting inquiry-based learning in mathematics and science illustrate this move. Following the idea of a traditional worksheet, a dynamic worksheet is a document written in HTML that includes applets to be viewed at the computer screen. This technical basis enables the integration of texts, graphics and dynamic configurations. The learning environment can productively combine experiments on the computer screen with more traditional paper and pen work when the students have to put down notes and sketches in their study journals. The potential offered by ICT for supporting inquiry-based practices in mathematics and science education, for moving from local to global influences and successes, is thus substantially transformed; in Fibonacci, we use ICT to improve inquiry-based education. This being said, we would like to stress some important points. ICT offers evident potential for supporting inquiry-based learning in mathematics and science. This does not mean that ICT tools must be given a predominant role.

Experimental work can and must also develop with more classical objects and technologies. Virtual experiments should not replace real experiments. These are especially important for approaching new fields, new domains of experience. For instance, an adequate development of spatial and geometrical knowledge with young students cannot just be achieved by using a Dynamic Geometry Software (DGS), whatever is the quality of this use. It also requires working with objects and models in different spaces, not just in the micro-space of the sheet of paper or the computer screen.

ICT offers evident potential but actualizing this potential requires appropriate tasks and guidance of the teacher. As shown by research developed in that area, real creativity must be developed in terms of tasks, and not just adaptation to the ICT environment of tasks which have proved to be effective in more standard environments. This makes the collective elaboration and exchange of resources in Fibonacci especially important. The same can be said regarding teachers’ practices. Benefiting from the learning potential of ICT technology requires from the teachers new forms of orchestration and guidance whose requirements have been underestimated until recently.

In summary, ICT creates today a new ecology for inquiry-based education in mathematics and science education, that the Fibonacci project must take into consideration, without underestimating what a productive use of ICT requires in terms of design and teacher expertise. (Adapted from Fibonacci Project, section Reference).

If you're interested in using ICT to support the full Inquiry process, you should consider exploring the www.nquire.org.uk, discussed in the context of use here, and another OU tool - Enquiry Blogger.

See also resources xyz

You might also like to look at this EARLI page which lists software packages for teaching (go to 'edit'->'find' on your menu bar, and search for 'inquiry' to find relevant software.

Inquiry for Professional Development

The DfE links to an Australian report 'Towards a Culture of Inquiry' which provides a useful summary.