Speaking and Listening in Group Work

- Aspects Of Engagement

- Assessment Overview

- Assessment for Learning Introduction

- Assessment for Learning Research Summary

- Building Capacity in School

- Classroom Management - Thinking Point

- Creating Engagement

- Developing Higher Order Scientific Enquiry Skills

- Developing Your Teaching

- Factors Affecting Lesson Design

- Fibonacci Project

- Group Talk - Benefits for Science Teaching

- Group Work - Practical Considerations

- Group Work - Research Summary

- Improving Reading - Research Summary

- Improving Writing - Research Summary

- Inclusive Teaching in Mathematics

- Inclusive Teaching in Science

- Modelling Introduction

- Purposes and characteristics of whole-class dialogue

- Questioning Research Summary

- Speaking and Listening in Group Work

- TESSA Working With Teachers

- Teaching Learning Developing Approaches to CPD

- Teaching Learning and Whole School Improvement

- The Importance of Speaking and Listening

- The Process of Lesson Design

- The educational value of dialogic talk in whole-class dialogue

- The impact of enquiry-based science teaching on students' attitudes and achievement

- Types Of Question

- Using Digital Video in Professional Development

- Whole Class Work - Research Summary

This resource is licenced under an Open Government Licence (OGL).

This resource is an adapted version of an Initial Teacher Education - English resource, the original of which is available at: http://www.ite.org.uk/ite_topics/speaking_listening_reception/001.html

Speaking and Listening at Reception and Key Stage 1

| Jennifer Logue

Senior Lecturer Department of Childhood and Primary Studies University of Strathclyde |

1 Introduction

Developing Speaking and Listening at Reception and Key Stage 1 will involve children in a range of experiences some of which may be incidental and occur as part of ongoing involvement in play. However, such is the potential of group talk in supporting learning that it cannot always be left to chance. As well as encouraging students to engender an enabling classroom ethos for talk, they will need support in planning opportunities for children to collaborate to construct meaning together.

In teaching students about speaking and listening it is important to mirror good classroom practice in this area. Students are therefore encouraged to collaborate in small groups to explore issues and deepen their learning. The web pages focus on supporting students in forming groups and devising tasks for talk as these are problematic areas for students in the development of speaking and listening. These are also aspects which are often unplanned for resulting in learning being inhibited rather than promoted Blatchford & Kutnick (2003).

2 Forming Groups

Often students are keen to implement group talk activities in the classroom but are unsure about how to group children for these activities. We are keen that group talk takes place as a way of learning in all areas of the curriculum and this can present further uncertainty as children may already be grouped in attainment groups, social groups etc. It is especially important that this is explored with students as the success of group talk is contingent upon group size and composition

2 Forming Groups

2.1 Group Size

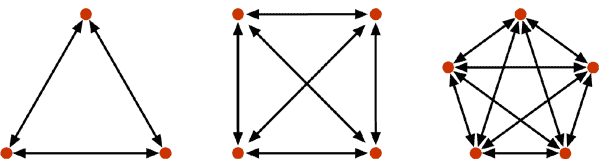

Before any examination of how to group children for talk activities, it is essential to consider with students the optimum number of children who can usefully talk in each group. Faced with classes where children may be seated in groups of 6, 8, 10, students may be tempted to set up group talk for groups of similar numbers. Guidance is fairly clear that groups of four allow for a range of ideas without the lines of communication becoming too complicated. Figure 6.3 in Bennett & Dunne (1994) is useful in exemplifying the lines of communication in groups of 3 to 5 children. See below.

There is also advice maintaining that pairs can work well together as it is difficult not to respond to one other person and this is well worth students considering for children at Foundation stage and KS1.

2 Forming Groups

2.2 Group Composition

2.2.1 Criteria for Forming Groups

A useful starting point in exploring how groups of four might be established is in asking groups of students to select and rank six criteria for forming groups from the possibilities listed below, adding any others they might think of.

- Ability to write

- Ability to Read

- Friendship

- Imagination

- Ability to Listen

- General Knowledge

Students are then asked to work on their own to read the quotes below related to forming groups. They should then regroup to review their selection and ranking of criteria for forming groups in light of their reading. The suggestion would be that no matter whether children were grouped in attainment groups in, e.g. Mathematics or mixed attainment groups in, e.g. Science, personality is central to decision making when forming groups. Further to this, it is likely that more effective collaboration will be experienced in groups where similar personalities are grouped together. This idea can often take students by surprise as they initially regard mixing personalities as a ‘fairer’ way of organising groups.

Personality …reluctant or hesitant speakers may feel able to participate when their more confident peers are absent, whereas dominant pupils put together may benefit from learning to cope with the contribution of those with similar traits. Holderness & Lalljee (1998)

…extrovert personalities are more likely to interact in small groups and introverts are less likely to interact.Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

Gender Tann’s (1991) experimental structuring of collaborative tasks used mixed-gender groups and found boys to be argumentative in discussion, while girls tried to reach agreement in a more consensual manner. Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

She (Webb 1991) found that an imbalance in number of boys and girls leads to gender differences similar to those found by Tann, but recommends equal numbers of boys and girls in each group to achieve balance in discussion and successful problem solving.Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

Girls will often participate more freely in a technology or science task without the presence of boys. Holderness & Lalljee (1998)

Friendship Friendship, thus, may limit achievement in problem-solving tasks and general development of co-operative skills in the classroom. Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

…groups of close friends may take so much for granted about each other that they are not able to talk in an exploratory or open way, or to be explicit about their thinking with each other- they may tend to leave much unsaid. Howe (1997)

Friends tend to agree with one another on principle, and less confident children make no contribution at all, to avoid being held responsible later on. Grugeon, Hubbard, Smith & Dawes (1998)

Attainment Groups function best when they are of mixed ability but such groups must include pupils from the highest ability groups within the class. Galton & Williamson (1992)

Homogeneous high-ability groups do not display high-level elaborative interactions when asked to jointly solve a problem; most pupils want to work as individuals. Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

Homogeneous low-ability groups have little stimulus (from more knowledgeable group members) for high-order elaborative interactions and much of their interaction is off task. Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

Webb’s evidence concerning heterogeneous/mixed ability groups finds that these groups were more likely to use high elaborative interactions leading to problem solving achievement. Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

Bilingualism There may be times when a bilingual group will enable pupils to use a shared home language, providing mutual support, while at other times a mixed language group may provide a necessary stimulus. Holderness & Lalljee (1998)

2 Forming Groups

2.2 Group Composition

2.2.2 Planning for group size and composition

To pull the aspects of group size and composition together, the following scenario can be given to groups of students to consider, having firstly given time for individuals to think about it on their own. As part of their deliberations, students should be guided to read differing views on the advantages and disadvantages of appointing a group leader.

Scenario Ms Borland thinks that the History curriculum provides a useful context for the development of speaking and listening. She has therefore begun to incorporate more group talk activities into her topics. She has noticed in one of the groups that out of 6 children only three participate to any great extent. She has decided that she will appoint a group leader in the hope that it will encourage wider participation.

- Why might a limited number of children be participating in the talking tasks?

- To what extent do you think her idea about appointing a group leader will encourage greater participation?

- What other options could the teacher consider to increase participation?

3 Structuring Tasks Within A Curricular Context

Introduction

The pressure in schools for balance and breadth and the higher profile of other forms of language can mean that some teachers allocate infrequent, isolated periods of time for group talk, or worse, relegate it to the ‘it would be nice to do it if only I had the time’ agenda. It is important that students see the potential for group talk as a means of learning in all curricular areas rather than a rarely timetabled part of the Language curriculum alone. 3.1 The potential of group talk

To help to convince students of the power of group talk in children’s learning, it is useful to have them view a video clip or examine a transcript of children talking. The transcript included below from Grugeon et al (2005) can be used for this, or, indeed, any other extract where children are grappling with meaning in a purposeful task. Students should be issued with the transcript and asked in pairs to consider how children are helping one another to make meaning. Students should also be provided with the accompanying table as a starting point to help them analyse the children’s talk.

Transcript: Three children in a lower school, 7 and 6 years old, discuss snails in a snailery, without their teacher present

| Susan: | Yes, look at this one, it's come ever so far. This one's stopped for a little rest ... |

| Jason: | It's going again! |

| Susan: | Mmmm good! |

| Emma: | This one's smoothing ... slowly |

| Jason: | Look, they've bumped into each other (laughter) |

| Emma: | It's sort of like got four antlers |

| Susan: | Where? |

| Emma: | Look! I can see their eyes |

| Susan: | Well, they're not exactly eyes ... they're a second load of feelers really aren't they? No . . . and they grow bigger you know ... and at first you couldn't hardly see the feelers and then they start to grow bigger, look |

| Emma: | Look ... look at this one he's really come ... out ... now |

| Jason: | It's got water on it when they move |

| Susan: | Yes, they make a trail, no let him move and we see the trail afterwards ... |

| Emma: | I think it's oil from the skin |

| Jason: | Mmm ... it's probably moisture ... See, he's making a little trail where he's been ... they ... walk very ... slowly |

| Susan: | Yes, Jason, this one's doing the same, that's why they say slow as a snail |

| Emma: | Ooh look, see if it can move the pot ... |

| Jason: | Doesn't seem to |

| Susan: | Doesn't like it in the p… when it moves in the pot ... look, get him out! |

| Jason: | Don't you dare pull its shell off |

| Emma: | You'll pull its thing off shell off … ooh it's horrible! |

| Jason: | Oh look ... all this water! |

Analysing the children’s talk

| Collaborative Meaning Making | Examples from Extract |

|---|---|

| Questioning | |

| Disagreeing | |

| Extending | |

| Qualifying | |

| Changing Views | |

| Revisiting Ideas |

Adapted from: p.7 Handbook, DfES (2003) Speaking, Listening, Learning: working with children in Key Stages 1 and 2, Primary National Strategy.

3.2 Identifying talking tasks across the curriculum

While there are useful techniques which will help students structure good talking tasks for children, and which will be considered subsequently, undertaking the following activity can de-mystify the notion of what talking tasks look like in different curricular areas. This is particularly important when students are placed in classes where individual written tasks predominate and there are few opportunities to experience children working on talking tasks across the curriculum.

It can be helpful, initially, for students to identify opportunities for talk under two broad headings: presentational talk and exploratory talk. Students should be aware that presentational talk tends to occur when the child is speaking to an ‘audience’, offering their ideas for display and evaluation. This type of talk is often more polished and complete. Exploratory talk helps children work on their understanding by allowing them to hear how their ideas sound and letting them modify their ideas in response to others.

Students should be provided with a copy of the table below and asked to work in groups to identify the type of talk which is likely to be the main focus of each of the tasks. They should then consider in which curricular area each of the talking tasks might be undertaken.

Examining Talking Tasks

| Talking tasks | ||

| Explaining how to make a wax resist painting | ||

| Using a plan to select suitable locations for the litter bins in the playground | ||

| Choosing a verse for a new baby card | ||

| Describing the visit to the fire station | ||

| Reporting the results of a floating/sinking experiment | ||

| Devising a true/false shape quiz | ||

| Recommending a book for a 5 year olds birthday | ||

| Planning a survey about items to sell in the tuck shop |

| Type | Curricular Areas |

| Presentational Talk (P) Exploratory Talk (E) |

# Language

|

3.3 Features of effective talking tasks

Many students find it difficult to plan effective group talk tasks. This is perhaps not surprising given what has been suggested earlier about the dearth of such tasks in many classrooms. To support students with their planning it is important to identify what the features of a good talking task are. That is to say, tasks with which children stay engaged, the talk is task related and children’ thinking is developed. This process can be started by asking groups to compare two tasks to derive what makes one task more likely to maintain involvement than the other. The tasks outlined below, based on Inga Moore’s book ‘Six Dinner Sid’, published by Hodder Children’s Books, should help students to do this.

Here are two tasks, Task A and Task B, which apparently cover the same content. Students should be given both tasks and asked to decide which one would be more likely to encourage children to talk in groups effectively. Hopefully, they will go for Task B! Students should now focus on Task B and identify at least 3 features which make it more effective.

Task A — Six Dinner Sid Equipment for Sid One of Sid’s owners is going to the pet shop for things she needs for Sid. Make a list of things she should buy.

Task B — Six Dinner Sid Equipment for Sid One of Sid’s owners is going to the pet shop for things she needs for Sid. There are lots of things to choose from, but Sid’s owner can’t buy them all at once.

Sort out the items into things she should buy today, things she should buy later and things she doesn’t need to buy at all.

Decide on 3 things she should buy today. Make a list of these things.

(Cut into heading for children to use for sorting)

(Using actual items or photographs / pictures of items)

Features common to both tasks

- There is a real or realistic purpose to the task

- The children have enough knowledge to talk about the topic

- The task builds on previous learning experiences

- There is a clear outcome

- The task is open enough to allow for a diversity of views (however in Task A this may lead to disputational or cumulative talk rather than exploratory talk, Grugeon, Dawes, Smith & Hubbard (2005)).

Features more specific to Task B

- The children's curiosity will be aroused

- The children need to talk to produce a satisfactory outcome

- The task resources are presented in ways which will enable children to modify opinions, add suggestions, change their minds etc. in light of the discussion

- There is a problem or dilemma; something to be worked out

3.4 Using task structures

The list of task structures below, adapted from Gavienas & Logue (2004), will help take students to the next stage in planning their own talking tasks.

Task structures

- Add to/amend/remove/select items from a given list.

- Group statement about something under given headings.

- Categorise and devise headings for statements, objects and so on.

- Prioritise statements, steps, procedures and so on.

- Note pros/cons of given features of objects, items and so on (e.g. the safety, appeal, texture, colour of babies’ toys).

- Sort statements into, e.g. agree/disagree/can’t decide or true/false.

- Give precise criteria for children to adhere to, e.g. captions have no more than six words.

- Compare two things under given headings.

- Choose from options and justify choices.

- Convert from one form to another, e.g. text to map, diagram to 3-D model, text to illustration.

- Order items, procedures, events and so on according to given or agreed criteria.

- Organise pictures, items, statements onto a continuum, e.g. most favourite - least favourite

Students should be given time to work in groups to restructure the following task using the list above.

Six Dinner Sid A Name for the New Cat One of Sid’s owners has decided to get another cat to keep Sid company. Think of a name for the new cat.

If these are displayed on large sheets of paper students can identify which task structures have been used from the 1-12 above and compare the different ways tasks have been restructured.

3.5 Analysing talking tasks

To widen students’ experience of the different forms talking tasks might take, the chapter Who’s Asking The Questions? Hunt N, & Luck C, in Use of Language Across the Curriculum Bearne E, ed. (1998) should be read and summarised in relation to the structures and groupings used by a teacher undertaking a history topic. This will also reinforce the idea that speaking and listening activities should be an integral part of the curriculum which should be regularly planned for. The grid might be useful to help students’ notetake as they read.

“Who’s Asking the Questions?”

| Talking task | ||

| 1. | ||

| 2. | ||

| 3. | ||

| 4. | ||

| 5. | ||

| 6. | ||

| 7. |

Students could usefully deepen their understanding in relation to designing group tasks by reading Bennett & Dunne (1994) chapters 4&5, Designing tasks: Cognitive aspects and Social aspects and Sue Lyle’s chapter, Sorting out learning through group talk, in Goodwin (2001).

Once students have undertaken their reading, groups could be given a range of examples of talking tasks gleaned from different sources and asked to arrange them on an effective / less effective continuum. This should generate discussion and develop understandings about when loose or tight frameworks Bennett & Dunne (1994) might be more appropriate for the stage and context children are working at.

4 Other ideas for speaking and listening

- The Scholastic series, ‘Speaking and Listening in Cross Curricular Contexts’ published in 2004, provides a wealth of ideas for talking tasks related to national curriculum topics in Geography, History and Science at KS1 & 2. Students are finding these books to be invaluable resources on school placements from Reception to Year 6.

- ‘Teaching Citizenship through Traditional Tales (2003) Ellis, S. & Grogan, D. published by Scholastic, provides opportunities for group talk through thought-provoking letters from fictional characters allowing children to explore moral issues within the safe environment of fictional tales.

- SCCC (1998) provides support for students in developing children’s speaking and listening by suggesting possible next steps in ‘Assessment in the Classroom: Listening and Talking’.