Pedagogy and ICT a Review of the Literature

- Aspects Of Engagement

- Assessment Overview

- Assessment for Learning Introduction

- Assessment for Learning Research Summary

- Building Capacity in School

- Classroom Management - Thinking Point

- Creating Engagement

- Developing Higher Order Scientific Enquiry Skills

- Developing Your Teaching

- Factors Affecting Lesson Design

- Fibonacci Project

- Group Talk - Benefits for Science Teaching

- Group Work - Practical Considerations

- Group Work - Research Summary

- Improving Reading - Research Summary

- Improving Writing - Research Summary

- Inclusive Teaching in Mathematics

- Inclusive Teaching in Science

- Modelling Introduction

- Purposes and characteristics of whole-class dialogue

- Questioning Research Summary

- Speaking and Listening in Group Work

- TESSA Working With Teachers

- Teaching Learning Developing Approaches to CPD

- Teaching Learning and Whole School Improvement

- The Importance of Speaking and Listening

- The Process of Lesson Design

- The educational value of dialogic talk in whole-class dialogue

- The impact of enquiry-based science teaching on students' attitudes and achievement

- Types Of Question

- Using Digital Video in Professional Development

- Whole Class Work - Research Summary

This resource is licenced under an Open Government Licence (OGL).

This resource is available in editable (.doc) format File:Pedagogy and ICT a Review of the Literature.doc

Pedagogy and ICT: a Review of Literature

Avril Loveless

Education Research Centre, School of Education, University of Brighton.

© Crown copyright, 2010.

You may use and re-use the information featured in the publication(s) (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence - http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/.

Contents

Introduction 3

Section 1: Understandings of pedagogy 4

Section 2: Pedagogy and ICT 9

Section 3: Aspects of pedagogy and ICT 14

Section 4: Implications 20

References 22

Introduction

In 2003, the Becta publication ICT and Pedagogy presented a review of the literature which framed current understandings of pedagogy and the implications for the use of ICT in learning and teaching in formal educational settings (Cox et al., 2003). This 2009 review will revisit this topic in the light of more recent developments in understandings of pedagogy in practice and in policy initiatives and directions. It will attempt to offer frameworks for thinking about the ‘What?’, ‘How?' and 'Why?’ questions of teaching with information and communications technologies (ICT).

The ideas and research studies are presented by researchers and commentators who address the questions and challenges of pedagogy in different contexts and for different professional purposes. There are overlaps between them, as they are all attempts to describe and explain what we think pedagogy might be, and how we might find useful ways to ground our reasoning, decisions and activities in informed principles. In short, they are tools to help us to understand our teaching in local and global contexts, to help us, as Freire urged, to ‘read the world’ of our practice (Freire and Macedo, 1987).

An informal, ‘folk’ way of thinking about pedagogy is ‘What do teachers know, what do they believe and what do they do?’ The review attempts to help us to navigate our way through our thinking about the nature of knowledge; relationships between people, concepts and tools; understandings of pedagogical interactions and more recent thinking about pedagogy and design. It is underpinned by an understanding of pedagogy as relationship, conversation, reflection and action between teachers, learners, subjects and tools. It will outline some key approaches to understanding pedagogy in general and then consider pedagogy and ICT, illustrating particular issues with selected examples from the research literature.

Section 1: Understandings of pedagogy

1. 1. Pedagogy and teacher professional knowledge: refining our understanding

A useful synthesis of thinking about of the nature of pedagogy through its roots, traditions and interpretations is the work of Jenny Leach and her colleagues. ‘The Power of Pedagogy’ offers a thoughtful overview of research, scholarship and practice (Leach and Moon, 2008). The work starts with ‘the premise that good teachers are intellectually curious about pedagogy’ (p.1); addresses the understandings of the contextual, political and socio-cultural nature of pedagogy; and summarises the key themes of inter-related dimensions of pedagogy:

- Goals and purposes – how ideas are understood and shared by teachers and learners in a range of pedagogic settings

- Views of mind and knowledge – our understanding of what it means to ‘know’ and ‘be’ influences how we approach learners and what we think is appropriate for them to learn

- Views of learning and learners – our understanding of our views of mind and knowledge influences the ways in which we conduct our activities in pedagogic settings, from classrooms to chat rooms

- Learning and assessment activities – the design of these activities expresses all the dimensions, and the first three dimensions most explicitly

- Roles and relationships – the relationship between teachers and learners is reflected in the ways in which each, at different times and in different ways, is knowledgeable, in control, able to collaborate and contribute, respectful, and able to engage in learning

- Discourse – our language, behaviours and expectations play a role in expressing the cultures of different pedagogic settings

- Tools and technologies – artefacts and technologies are essential in our knowledge construction, and play a key role in our understanding of human learning as ‘Person-Plus’ (Perkins, 1993).

In earlier work (Banks et al., 1999), Banks, Leach and Moon proposed a model of teacher professional knowledge which drew upon a range of understandings of teacher knowledge (Shulman, 1987); intelligence (Gardner, 1993); situated learning (Lave and Wenger, 1991); transposition of subject knowledge (Chevellard, 2007); and overlapping identities in communities of practice (Wenger, 1998). The model has served to help teachers to identify the different elements and experiences in their teaching, and reflect upon the themes of identity and change in their practice. It is a model which highlights interaction, integration and complexity.

Shulman’s earlier work (1987) described seven different characteristics of teacher knowledge. He describes teachers' practice as drawing upon a ‘learned’ professional knowledge base built up from seven elements:

- Knowledge of subject matter, or content knowledge

- Pedagogical content knowledge, or the ways of representing subject knowledge appropriately for learners

- Knowledge of curriculum, or the grasp of the materials, resources and ‘tools of the trade’ available to the teacher

- General pedagogical knowledge, or the broad understanding of management and organisation

- Knowledge of learners and their characteristics

- Knowledge of educational contexts, ranging from groupings, classrooms, schools, education authorities, national policies to wider communities and cultures

- Knowledge of educational aims, purposes and values.

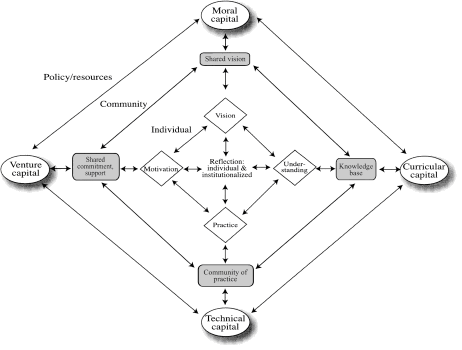

Discussing the nature of knowledge is always challenging, as our understandings and descriptions of ‘professional knowing’ are not always clearly defined. The view of knowing underpinning this review is socio-cultural, situated in social and physical contexts, mediated, complex and interpreted. Some research which draws upon Shulman’s early discussions of the dimensions of teacher knowledge, including pedagogical content knowledge, does not always explicitly acknowledge the underlying theory of knowledge, nor Shulman’s later recognition of the more situated and complex understandings of knowledge. He accepted critiques of his work as focused on teachers as isolated individuals and his later work addresses the nature of professional knowledge which enables teachers to be ‘ready, willing and able’ to teach, locating individuals clearly within the communities in which they act, and the wider policy and resource contexts in which they practise (Shulman and Shulman, 2004). His later studies acknowledge the ‘capital’ of the social, cultural and political contexts in which learning and teaching take place, and draws attention to the complex interactions and relationships between teachers, learners, knowledge domains, communities and wider factors (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Levels of analysis: individual, community and policy, from Shulman and Shulman 2004, p.268

1. 2 Pedagogy and Design

Watkins and Mortimore (1999, p.17) offered a definition of pedagogy as ‘any conscious activity by one person designed to enhance learning in another’. Design for learning encapsulates contemporary understandings of teaching which focus on a ‘systematic approach with rules based on evidence, and a set of contextualised practices that are constantly adapting to circumstances’ (Beetham and Sharpe, 2007, p.6). Good pedagogical design needs to express the congruence between the content, teaching strategies, learning environment, assessment and feedback, and all of these reflect underlying theories of learning and value (Mayes and de Freitas, 2007).

The implications of thinking of design in pedagogy are echoed in recent thinking and research which elaborate upon European understandings of ‘Didaktik’, a concept which is not clearly reflected in Anglo-American traditions of approaches to teaching and learning. Didaktik can be described as the focus on the planned support for learning to acquire Bildung, which is often translated as ‘formation, education or erudition’ in becoming an educated person able to engage purposefully in the world. Klafki (2000) identifies elements of Bildung as self-determination, co-determination, and solidarity, in which individuals’ rights and contributions to society are justified in association with helping others. Hudson (2007) draws attention to how Didaktik is therefore closely linked to universal, educational questions, placing the discussions of pedagogy clearly in wider social, cultural and political meanings for teachers and education systems.

The traditions of Didaktik highlight the ‘What?’, ‘How?’ and ‘Why?’ questions of teaching. The ‘What?’ questions relate to content and subject knowledge which themselves are contested in our understanding of subject domains and how these are expressed in reviews of the curriculum. ‘How?’ questions relate to teaching styles, methods and strategies, described as ‘pedagogic knowledge’. The ‘Why?’ questions relate to the wider context of society, culture, politics and capital.

One of the ways in which understandings of Didaktik differ from earlier Anglo-American traditions of pedagogy, is in the approach to the ‘diffusion of knowledge’ in institutions and society through transpositions and transformations of knowing between teachers and learners, rather than transmission of information.

The basic principle of the didactic view of learning and teaching was that knowledge is not something given out there, so to speak, but something to be explained …[…]…Knowledge is not a given, the theory says, but built up, and transformed, and – such was the watchword – transposed. (Chevellard, 2007, p.132, emphasis as original)

Hillocks also described pedagogical content knowledge as ‘taking pains’ to represent and transform subject concepts appropriately for learners (Hillocks, 1999). It is this ‘taking pains’ in preparing to teach, that Klafki describes as ‘Didaktik analysis’. This process is itself ‘draft’ in nature, it is the design of opportunities and possibilities for pupils, and requires an openness of mind in the relationship between content, teacher and pupil. It is similar to the preparation for processes of creative improvisation in the moments in which teachers and pupils make conceptual connections within subject domains (Loveless, 2007).

Klafki’s approach to Didaktik analysis starts with the significance, meaning and value in preparing teaching activities grounded in relationship to learners:

- What wider or general sense of reality do these contents exemplify and open up for the learner? What basic phenomenon or fundamental principle, what law, criterion, problem, method, technique or attitude can be grasped by dealing with this content as an ‘example’?

- What significance does the content in question or the experience, knowledge, ability or skill to be acquired through this topic already possess in the minds of the learners?

- What constitutes the topic’s significance for the learner’s future?

- What is the structure of the content which has been placed into a specifically pedagogical perspective by questions 1 & 2?

- What are the special cases, phenomena, situations, experiments, persons, elements of aesthetic experience, and so forth, in terms of which the structure of the content in question can become interesting, stimulating, approachable, conceivable, or vivid for learners?

These questions root understandings of pedagogy in the ‘Why?’ questions, making critical connections with the wider landscapes of knowing in our society and time, embodying what is to be human through our teaching. Hudson (2007) describes how our growing familiarity with concepts of Didaktik has offered fresh perspectives on meaning and intentionality, attention to studying, recognising and holding complexity, tools for holding complexity, and the role of the teacher.

1.3 Pedagogy and ‘Person-Plus’

The role of tools and technologies in the design of learning environments and construction of knowledge has been supported by the recognition of the contribution of socio-cultural-historical theories of human activity. Somekh (2007) reflects on her career experience as a researcher engaged in questions of ICT and innovation, and draws attention to the use of these theoretical frames built upon Vygotsky’s concept of mediation of human action, embedded in culture, and distributed through dialogue with others and the use of artefacts and tools (Wertsch, 1998; Salomon, 1993; Perkins, 1993; Pea, 1993). David Perkins’ concept of ‘Person-plus’ helps to describe how tools and technologies play a role in distributed cognition, that is, people appear to think, not just in their own heads, but in partnership with others and with the help of tools and artefacts in the surrounding environment. Learning environments provide opportunities for knowledge storage, retrieval of information, representation, and construction of new knowledge. Our knowing is stored, made accessible and workable through the use of tools, from notebooks and pencils to databases, multimedia presentations and Twitter.

Our understandings of pedagogy have moved beyond Shulman’s early characteristics of teacher knowledge as static and located in the individual. They now incorporate understandings of the construction of knowledge through distributed cognition, design, interaction, integration, context, complexity, dialogue, conversation, concepts and relationships. Educators engaging in continuing professional development will acknowledge the importance of active practice, peer to peer sharing, wider professional networks, and reflection.

Section 2: Pedagogy and ICT

How then might we develop our understanding of the contribution and constraints that ICT tools and resources might bring in an approach to pedagogy which is constructive, interactive and complex? This section considers different elements in teachers’ pedagogical reasoning with ICT:

- The wider economic, social and cultural context which influences educational policy and the provision of ICT resources for learning and teaching

- Metaphors for ICT and the roles that digital technologies might play in teaching activities

- An understanding of the development of teacher knowledge with ICT, namely Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge.

2.1 Wider contexts for ICT in education

The question ‘Why use ICT?’ can be viewed at different levels in the economy, in society, and in education. The wider social, economic and policy context of ICT has an influence on strategies and resourcing for education, from the provision of ICT equipment in schools and designing schools for the future, to commissioning research in technology enhanced learning and providing CPD for practitioners (DfES, 2005; Becta, 2007; Carmichael, 2007).

Educators who can ‘read the world’ in which they teach and learn perceive that ICT might be important in their work for three different reasons, which themselves can be in tension:

- ICT as a social and cultural phenomenon

- ICT as a resource for learning and teaching

- ICT as a new field of concepts and affordances for learning and teaching.

The challenges to pedagogy lie in the weaving together of these three perceptions. It is, however, interesting to note that the use of ICT to support learning and for its own sake in the present moment of teaching, rather than as a rehearsal for vocational purposes, is not often the teachers’ first reported reason for using ICT in their work (Loveless, 2003).

Educators and researchers are interested to know more about how children and young people use digital technologies in their wider cultural lives and informal learning. As well as perceiving the economic implications for ICT in education, teachers make pedagogical decisions within the wider context of society and culture. It can be argued that the contemporary world of childhood and youth in developed countries is permeated by digital media which shape communication and interaction. These changes challenge our understanding of the digital divide, digital culture, digital safety and digital media literacy for young learners (Buckingham, 2007; Sefton-Green, 2006). Livingstone describes how technologies are becoming ‘embedded in the fabric of every activity – they are part of the infrastructure that supports learning, communication and participation’ (Livingstone, 2008, p.6). Coleman draws attention to lifespan developmental theory, which is a view of development which recognises the influence of context and choice, as much as biological determinism and linear stages in development. This is helpful in our understanding features of adolescents’ lives in which they are both mature and childlike at the same time, in different contexts. They demonstrate their growing agency and abilities to influence their own development rather than be passive receptacles of determined biology; their focus on social relationships within families and between friends; their growing mastery and autonomy in the physical and social world; and their explorations of identity. These experiences of growth and development might lead them to engage with many of the features offered by digital technologies, from game playing and programming, to social networking and blogging (Coleman, 2008).

It is important to recognise the place of our interest in technology in education within the wider landscape of economic, political and social change (Dale, 1999). The perception of ICT as a social and cultural phenomenon is echoed in UK Government policy initiatives, such Harnessing Technology (Becta, 2008), and the identification of trends affecting the use of technologies in learning, such as economic policy, globalisation, capital investment programmes, expanded children’s workforce, non-traditional education providers, and commercial technological innovations (Chowcat et al., 2008). Morgan and Williamson present an overview of a longer history of contexts for educational policy, discussing some of the contemporary connections between ‘neat capitalism’ and ‘neat schooling’, characterised by informality, social conscience, innovation, listening to ‘customers’, flexibility, and fun (Morgan and Williamson, 2008).

Kress and Pachler argue that digital technologies and media have shaped not only social and cultural contexts, but also approaches to, and environments for, learning. Their discussion of ‘mobile learning’ focuses not on the technologies, but on the changes in the ways we engage with information. Learning experiences can be more fluid, interactive and multimodal. They are more mobile, not because the technologies are necessarily mobile, but because the learner can be placed more centrally, given access to information and opportunities to make meanings in a variety of linked environments. Where the wider world is the curriculum, there are important questions to be asked about the place of individuals and communities within a neo-liberal view of markets in which ‘the possession of an education’ might be approached as a global commodity to be traded, rather than a quality of those individuals and communities (Kress and Pachler, 2007).

2. 2 Metaphors for ICT and pedagogy

The metaphors that have been used to describe the roles of ICT in pedagogical designs and activities are useful as they offer insights into how teachers and software designers understand the relationship between learners, teachers, knowledge and digital technologies. Stevenson (2008) discussed a model for pedagogy, based on Activity Theory, which highlighted these relationships between the rules, management and artefacts in a teaching activity. In 60 ‘snapshots’ of teachers and learners in schools, he identified four common metaphors of ICT as resource, tutor, tool and environment. The metaphors demonstrate different degrees of control, motivation, access and choice for learners and teachers.

The metaphor of ‘resource’ expressed the ways in which teachers had different digital technologies ‘to hand’, and were able to select them according to their needs. They were often used to reproduce or imitate other resources to support familiar or common practice in a non-digital curriculum, such as interactive whiteboards for presentation.

Using ICT as a ‘tutor’ draws upon learning theories which support a range of learning experiences, from practice of skills, to developing conceptual understanding. The ICT resources are designed to respond to and scaffold learners’ needs, and learners have more control and access and some degree of task choice. Early examples of such applications were the Integrated Learning Systems (ILS), but there is still work to be done to understand the learners’ contexts and how applications might adapt and adopt ‘intelligent’ strategies for dialogue and re-use (Ravenscroft and Cook, 2007).

ICT as an ‘environment’ was a useful metaphor with applications which provided ‘microworlds’ where learners could explore, build and present their understandings of different concepts, from programming in Logo to working with mathematical models or designing multimedia and hypertextual texts. Such microworlds are characterised by the high degree of learner control and autonomy, and are an intrinsic part of the conceptual learning process itself. The ‘environment’ metaphor encourages the approach to the ‘learner teaching the computer’, rather than the computer as a resource which teaches the learner.

The metaphor of ICT as a ‘tool’ is commonly used, although not always with a shared understanding of the possibilities of the term. ICT can be described as ‘just a tool’ to be picked up and used to do a task, rather like the resource. However digital technologies can also be used to support conceptual understanding and extend thinking. Jonasson’s description of applications such as spreadsheets, databases and simulations as ‘mindtools’, captures some of this more nuanced understanding of the role of tools in mediating and shaping activities (Jonassen, 2006). Recognising the potential and constraints of ICT as a tool which supports and shapes learning, requires teachers to have a knowledge of the subject domain and competence in the appropriate use of the technologies – a capability to ‘orchestrate the affordances and constraints in the setting’ (Kennewell, 2001, p.107).

2.3 Technological Pedagogic Content Knowledge

Cox et al. (2003) recognised the additional complexity in pedagogical reasoning when ICT resources are involved, whether that be as a resource, a tutor, an environment or a tool. The knowledge, skills and understanding that teachers require have long been a matter of interest, and there have been studies to explore the characteristics of teacher professional knowledge (see for example Kennewell, 1995 and Woollard, 2005).

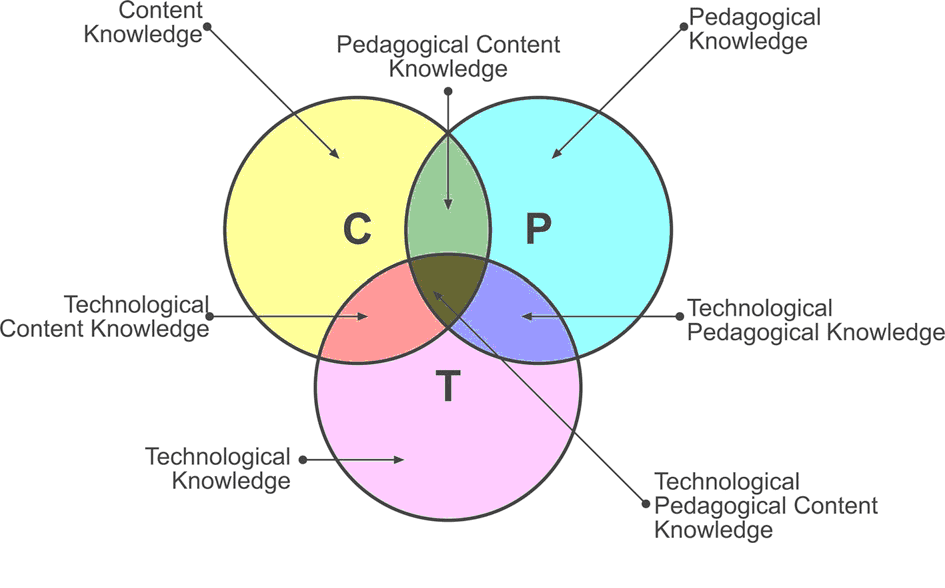

Koehler et al. offer a model to describe the interactive, relational nature of teacher knowledge which encompasses content, pedagogy and technology. Building on Shulman’s early framework, they conceptualise their model as ‘Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge’ (TPCK), and ‘argue that intelligent pedagogical uses of technology require the development of a complex, situated form of knowledge’ (Koehler et al., 2007, p.741)

Fig 2: The interaction of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK) from Koehler et al., 2007 p.742

This model is distinctive in its focus on multiple relationships and design, acknowledging that knowledge about technology cannot be separated from knowledge, teaching activities and contexts. The interaction between Pedagogy knowledge and Content results in Pedagogical Content Knowledge, similar to Shulman’s description of representation of concepts, pedagogical techniques, knowledge of learners’ conceptual understandings and difficulties, and theories of epistemology. Technology and Content produce Technological Content Knowledge, an understanding of the subject content being taught and how technology might be related to representing and shaping the concepts in the subject domain. Technology and Pedagogy contribute to Technological Pedagogical Knowledge, which offers an understanding not only of the range of ICT tools that might be used for a particular task, but also how to employ teaching strategies to use them to greatest effect.

The interaction of all three elements gives rise to Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge TPCK. Koehler et al. contend that

… good teaching with technology for a given content matter is complex and multi-dimensional. It requires understanding the representation and formulation of concepts using technologies; pedagogical techniques that utilize technologies in constructive ways to teach content; knowledge of what makes concepts difficult of easy to learn and how technology might address these issues; knowledge of students’ prior knowledge and theories of epistemology; and an understanding of how technologies can be utilized to build on existing knowledge and to develop new or strengthen old epistemologies. Clearly this knowledge is different from and greater than that of a disciplinary expert (say a mathematician or a historian), a technology expert (a computer scientist) and a pedagogical expert (an experienced educator)

(Koehler et al. 2007, p.743)

A critique and extension of the concept of TPCK is offered by Angeli and Valanides (2009). They suggest that the model described by Koehler et al. is general, but does not discuss how the potential and constraints of ICT tools might shape content and pedagogy. Using a word processor, for example, with its potential for editing, revision, and presentation, might change the experience of writing and composition, and challenge teachers to approach various processes and purposes of writing somewhat differently than with pen and paper. They argue that TPCK emerges from the interaction between pedagogy, content and technology and is new knowledge, which needs an explicit focus in order for teachers to make the connections between their knowledge and experiences.

The importance of developing a view of TPCK is also stressed by Ferdig, who discusses how innovations with technologies might be considered and measured to be ‘good’, that is, how successful they are in enabling learning in particular content tasks. Innovative technologies need to be linked to learning experiences by pedagogy which enables authenticity; ownership; active participation; relationships and roles within communities; creation of artefacts; reflection and feedback (Ferdig, 2006).

Section 3: Aspects of pedagogy and ICT

Previous sections offered a discussion of broad understandings of pedagogy, and a closer focus on how the presence and use of ICT changes the cultural context, the relationship and roles between teachers, learners and technologies, and descriptions of teachers' professional knowledge. This section will consider seven selected research studies which aimed to address particular questions of pedagogy with digital technologies, offering evidence to support some of the features of pedagogy and ICT outlined thus far.

The first, the Interactive Education Project focused on ICT and conceptual understanding within subject areas. The Pedagogy with E-Learning Resources project (PELRS) explored the changes in pedagogical strategies emerging from different approaches to roles of pupils and teachers and ICT tools. The following three studies focused on the different pedagogical use of specific digital technologies: the interactive whiteboard, mobile technologies and the virtual learning environment Moodle. The next project, ‘Learning Technology by Design’ studied how teachers developed TPCK through professional development opportunities to generate new knowledge. The final study focused on how experienced teachers adapted a proposed model of effective e-learning (MEEL).

3.1 The Interactive Education Project

The project, which was funded by the ESRC Teaching and Learning Research Programme, examined the relationship between ICT and learning in curriculum subjects in schools. A key focus was on the design of learning and teaching activities, where teachers and researchers worked together in Subject Design Initiatives (SDI) to identify how ICT might be used to support the teaching of concepts or topics which pupils often found difficult to understand. The design principles were grounded in three theoretical perspectives:

- The role of pedagogical content knowledge and teachers’ underlying beliefs about learning and knowledge

- The contribution of ‘workbench communities’ of small groups of teachers and researchers working together to solve pedagogical problems, using intellectual and material tools in ways which were interactive and interdependent

- The focus on intellectual activities of planning, enacting and reflecting upon teaching.

These perspectives reflected the approach of the project to design, ‘scaffolding’, and mutual recognition of expertise within the SDI communities, rather than a ‘top-down’ imposition of the model, or an unsupported exploration of ideas. The study identified a wide range of issues to be considered within subject cultures. There was a desire by teachers to develop their use of ICT tools purposefully, yet the pedagogic use of ICT often increased the complexity of learning and teaching in a subject. This did, however, afford opportunities for new approaches in thinking and engagement in the subject areas, and highlighted the strength of the role/s of the teacher. There was also a realisation of the unpredictable, often messy and open-ended nature of these ways of working to design and develop rich learning environments (see for example John and Sutherland, 2004; John and Sutherland, 2005; La Velle et al., 2007 and Gall and Breeze, 2005).

3.2 The Pedagogy with E-Learning Resources Project (PELRS)

This project, supported by the General Teaching Council, identified the theoretical framework for research with teachers designing and preparing their lessons in schools. Drawing upon Activity Theory as a planning frame, the project enabled teachers and researchers to develop their understanding of the contribution of ICT as a tool mediating purposeful activity to realise particular learning objectives (Pearson and Somekh, 2006). The project was predicated on the negotiation of expertise and roles in the partnership between pupils, teachers and researchers, whilst working within the requirements of the systems of curriculum and assessment frameworks. The pedagogic strategies which underpinned the action research were:

- Pupils as teachers

- Pupils as media producers

- Pupil voice, and

- Learning online.

After negotiating the learning objectives and outcomes, pupils were able to choose the ICT tools they needed in their learning activities for researching information, presenting their ideas and outcomes, and capturing the processes involved in the work. The focus on the learning outcomes of the project was on the development of creative learning, active citizenship, cognitive engagement, and meta-cognition, which were observed and reported by the project participants. Constraints on the full development of these ways of working were encountered through the restrictions in ICT infrastructure and access in schools, and the inflexibility of timetabled activities in many schools, particularly in the secondary phase (GTC, 2006). The pedagogic contribution of the ICT resources within this project was evident in the changes to ways of working between pupils and teachers, and the acknowledgement of pupil expertise in making and using choices with ICT tools (Somekh, 2007).

3.3 Interactive whiteboards

The claims for the ‘transformation’ of pedagogic practice stimulated by the introduction of interactive whiteboards (IWB) have been included in the enquiry of a variety of research projects. In a recent review of research literature Higgins et al. note that:

The research literature has yet to demonstrate the direction that teachers need to move to ensure that the proven changes the IWB can bring about in classroom discourse and pedagogy are translated into similar and positive changes in learning. (Higgins et al., 2007, p.221).

One particular study which focused on communicative and pedagogic practice drew on established research experience of teacher–pupil communications in classrooms (Gillen et al., 2007). The researchers examined the ways in which IWBs might shape or alter teacher–pupil interactions, active participation of pupils, and a shared frame of reference for building common knowledge. They also investigated the extent to which teachers used the affordances of IWBs to realise their pedagogic goals. Observation and interview data were analysed from the work of two primary school teachers, both of whom were confident in the use of IWB in their classrooms in familiar English and science lessons. Using a matrix of types of communicative approaches in teacher-talk – dialogic/authoritative and interactive/non-interactive – the analysis examined whether the use of the IWB changed pedagogy, or supported conventional teaching practices. The observations noted the use of authentic, visual resources of digital pictures; the facility of ‘block-reveal’ to structure and pace the lesson; the capacity to modify and save a presentation in the light of children’s feedback; pupil involvement in conventional initiation-response-feedback exchange; and risk-taking to learn from misconceptions and errors. The researchers saw evidence of some changes in pedagogy in the possibilities for open discussions with pupils, modification of prepared resources, and managing public risk taking. They also observed ‘technical interactivity’ in the use of the IWB to support the presentation of the teachers’ planned activities and management of resources of good quality and variety, without much change to conventional teaching strategies. The IWB was used effectively through the teachers’ ‘striking a balance between providing a clear structure for a well-resourced lesson and retaining the capacity for more spontaneous or provisional adaptation of the lesson as it proceeds’ rather than a ‘transformation’ (Gillen et al., 2007, p.254).

3.4 Mobile technologies

A review of literature in mobile technologies and learning identified some key themes that educators might find challenging, but might recognise and incorporate into pedagogic design and teaching strategies. Gathering contextual information might cross boundaries of privacy or anonymity; mobility and access beyond traditional classrooms might take learners into unplanned places; mobile learning experiences over periods of time and extent of place might need to be captured, organised and retrieved meaningfully; informality and authenticity might be threatened if the boundaries of students’ social networks are crossed or invaded by formal educational activities; and ownership and control of personal technologies might pose challenges in formal educational settings such as classrooms (Naismith et al., 2004). Subsequent research studies highlight the potential that mobile and wireless technologies offer for the intensification of connections between learners and the extension of learning communities and contexts (Roschelle et al., 2005).

One study evaluated the use of mobile technologies with mediascape resources, which provide opportunities for learners to develop a sense of place through making connections and associations whilst moving through and engaging with physical spaces (Loveless et al., 2008). Mediascapes are collections of location-sensitive texts, sounds and images that are geo-tagged or ‘attached to’ the local landscape, and learners use mobile technologies, such as PDAs, to roam in a space to detect and respond to these multimedia tags. ‘Create-A-Scape’ is a toolkit designed for teachers and pupils to plan and create mediascapes, attaching location-sensitive texts, sounds and images on a ‘digital canvas’ mapped onto a local landscape.

After a survey of general use, the study explored how five teachers in a variety of primary and secondary phase settings expressed their professional knowledge with this innovation. Interview and observation data were analysed within theoretical frameworks of creativity, sense of place and teacher knowledge. In this third theme, the pedagogical implications and possibilities for such mobile resources emerged. The teachers and advisors designed an imaginative variety of mediascapes, from fantasy worlds of treasure islands and moonwalks, to digital guides to the local campus and area. The teachers were secure in their content knowledge – literacy, geography, mathematics, science, PSHE, drama, ICT – and able to make connections between them to offer conceptual challenges for the learners. They demonstrated sophisticated teaching strategies as the pupils roamed beyond the familiar contexts of classroom and curriculum. The teachers also acknowledged their place in a wider community and network of teachers, technicians and national organisations, such as Futurelab, which offered support. Their ideas were realised as a balance between formal policy initiatives, such as ‘Fast Track’ or ‘personalisation’, and more marginal and creative possibilities for themselves and for the pupils. The innovations with the mobile devices challenged many aspects of the teachers’ familiar practice, yet they were confident and able to take risks to explore their ideas. Shulman and Shulman described the importance of ‘the teacher as curriculum interpreter and adapter as well as curriculum user’ as central to curriculum and pedagogy reform (2004).

3.5 Online presence

Recent research in VLEs, social networking and Web 2.0 technologies, recognises the tensions between the open-ended, collaborative and somewhat anarchic characteristics of the use of the social web, and the demands of more structured, guided and authoritative pedagogy. Crook asserts that such technologies are not usefully seen as replacements for educational interpersonal interactions (Crook, 2008). A range of studies suggest that a ‘reconfiguration of learning practices’, rather than claims for transformation, might be a fruitful way forward in research, exploring ways to ‘embrace features such as greater openness, personalization, creativity and collaboration without debunking pedagogy, structure and even constraint’ (Ravenscroft, 2009, p.4).

An ongoing study of pedagogical presence in online spaces, focused on student teachers’ developing their understanding of their roles in learning dialogues with pupils (Turvey, 2008). Student teachers were supported in reflecting on their pedagogical strategies in online conversations by considering the differences between informal, every-day communications online and those supporting more structured learning and teaching activities. The Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) Moodle was used as part of a project in which student teacher ICT specialists worked with a class of 9–10-year-old children with online and face-to-face activities, focusing on the theme of bullying. Analysis of online communications and interviews with student teachers identified two themes: the students’ use of strategies for ‘pedagogical presence’ online, and their perceptions of the value of the activity. The student teachers were observed to adopt a pedagogical presence to facilitate the discourse through activities such as summarising discussion, referring back to children’s earlier ideas, praising, justifying ideas, challenging children’s views or asking rhetorical questions. There were, however, limitations in the use of probing questions and the recognition of pacing and timing to make interventions which might have fostered a greater level or depth in the pupils’ thinking about the topic. This may indicate the student teachers’ lack of experience, but offers opportunities for them to analyse and reflect upon the nature of their online dialogue in such a structured exchange. When the student teachers reflected on their perceptions of the value of the online activity, some saw its contribution within a wider classroom discourse, whilst others focused on the activity with Moodle as a more isolated activity. It was noticeable that some of the students were more familiar than others with social networking activities beyond formal education settings, and were able to adopt these practices within their pedagogical repertoire in a more authentic manner.

3.6 Learning technology by design

Koehler et al present an approach to developing teacher knowledge, tracking and representing TPCK through ‘learning technology by design’, encouraging educators to learn how to learn and how to think about technology in their pedagogic practice. The research project involved Higher Education tutors who wanted to develop online courses in the College of Education. The small-scale study worked with two groups of tutors and students, analysing episodes of discussion and activity associated with pedagogic design. The categories comprising TPCK were therefore represented in terms of frequency and also in the conversational changes over time within the groups. The two groups demonstrated differences in the development of their pedagogical conversations. One group developed a noticeably stronger integration of pedagogy, content and technology than the other. The first had identified the focus on content early in the process, and all members of the group worked in partnership to solve the problems and resolve the activity. The second took more time to identify the purpose and content of the activity, and did not negotiate the roles of the group as openly. The researchers discussed the importance of the TPCK emerging over time, in collaboration and through active engagement with relevant and authentic professional tasks (Koehler et al., 2007).

Angeli and Valanides (2009) developed the idea of TPCK being new knowledge, in a study using ‘Technology Mapping’, a technique to help student teachers make some connections between the content and the pedagogical approach when designing teaching activities. The activity focused thinking, and also provided assessment feedback between experts, peers and self-evaluation in the process of designing technology-enhanced learning. However, they acknowledge that the development of TPCK was not an easy task for the student teachers in the early phases of their professional experience.

3.7 Validating a model for pedagogy and ICT across phases

Mayes and De Freitas pay attention to the implications of theories of learning and their expression in pedagogical design, and describe different models of pedagogy according to the priorities emerging from their theoretical basis – associative, cognitive and situative. (Mayes and de Freitas, 2007). De Freitas et al. worked with teachers from primary, secondary, post-compulsory, HE and community settings to study the response to and validity of a model of pedagogy developed by Becta – Modelling Effective E-Learning (MEEL). The model was a work-in-progress, intended to support planning and development for practitioners and institutions. The participants in the research engaged in activities which helped them to articulate and represent the range of processes involved in pedagogical design, and the relationships between those processes. Although the presentation of the model itself was reported to be rather abstract and static, the discussion itself enabled the practitioners to describe the starting points and aims of their pedagogy in their own words and to reflect their priorities within their own sectors. The value in the activity lay, not so much in the application of a standard model, but in the process of engaging with and making sense of its elements in relation to the teachers’ professional knowledge and context. The study indicated that a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to modelling pedagogy might not be appropriate, but that offering opportunities to recognise teachers’ knowledge and their willingness to engage with adapting and creating representations of their practice was helpful (De Freitas et al., 2008).

3.8 Summary

These selected studies suggest that ICT is more than ‘just a tool’, and contributes disruptive, distinctive, relationships in pedagogical activities. In preparing to use ICT, teachers’ pedagogical reasoning needs to take into account the wider subject and community contexts for the learning experience; the expertise and roles of all participants; and the affordances of the technologies for particular purposes. Models of pedagogy need to be relevant, grounded in teacher experience, flexible, complex and open to reflection and adaptation.

Section 4: Implications

Our understandings of pedagogy encompass the relationships between what we teach, how we teach it, and why it matters in our communities, societies and times. In this review I have argued that information and communication technologies can be viewed as tools that shape these three dimensions to our practice as educators: in the curriculum that we teach (What?); in the local strategies that we employ (How?); and in the wider physical, social and cultural contexts in which we teach (Why?).

Over thirty years, teacher education – from initial teacher training to continuing professional development in all sectors – has grappled with the challenges of supporting educators in their preparation to use ICT purposefully in their work. Shulman and Shulman’s framework can help us to think about the implications of our understandings of pedagogy for the development of the practice of the education workforce – to enable educators to be ‘ready, willing and able’, as discussed in Section 1 (see Figure 1).

Harnessing Technology: Next Generation Learning presents the national strategy for technology in education and skills (Becta, 2008). It contributes to the wider context of ‘capital’ provided in policy and resources, and is part of the backdrop to the economic, social and cultural landscape within which educators engage in learning and teaching. The strategy’s focus is clearly on technology as a tool for learning in times of change, and the systemic, organisational and individual demands that places upon the educational workforce. The connections between the aims of the strategy, and the questions about why they matter in the wider purposes of education, curriculum, pedagogy and assessment can be explored with learning professionals. Such questions also lead to discussion of the nature and purpose of the curriculum that is designed and offered at this level of ‘capital’.

At the community level, there is a recognition that learning professionals are situated in communities of practice which share knowledge and understanding in action. As individuals they contribute to and shape their various communities, just as they are influenced and shaped by being members of those communities. Such communities of educators are both formal and institutional, such as within a school or professional association; and informal and unbounded, such as the Mirandanet community or a social network focused on professional concerns. The community ‘knowledge base’ is interactive and complex, as discussed in Section 2 and indicated in Fig 2. As the examples in Section 3 illustrate, planning the use of ICT to enhance learning and teaching includes an understanding of how ICT tools might support design for learning in particular subject content areas as well as in general processes, roles and strategies in learning and teaching.

The individual level integrates all three dimensions of 'Why?', 'What?' and 'How?'. The vision and motivation of educators is grounded in their beliefs about why they think their practice matters, and how they can best design experiences and environments for learners. Their understanding of the use of ICT tools is influenced by their theories of learning, which are themselves dynamic and changing as our theoretical frameworks develop. Significantly different approaches to pedagogy and ICT will emerge from an understanding of ICT as ‘just a tool’ to mimic a familiar task, rather than an ecological understanding of people in learning environments with digital technologies which shape the nature of the task itself (Luckin, 2008). Educators need to relate examples of ‘good practice’ to the reality and materiality of their own contexts and experiences, and Selwyn reminds us that it is important to try to understand the ‘state of the actual’ and recognise different ways in which we might look at educational technology and its place in learning and teaching (Selwyn, 2008).

Within an approach to pedagogy which recognises the complex relationship between content, context, tools and people, our understandings of ‘e-maturity’ of individuals and communities might not necessarily be static or staged. Educators’ capabilities and competences with ICT tools will be related to both individual and community factors, and learning professionals can be more or less capable in different contexts at different times (Benzie, 2000). There are concerns that models of professional development which focus on technical competences without pedagogical context is ‘retooling’ teachers for specific tasks, rather than engaging in more substantial nature of pedagogy (Watson, 2001). Fisher et al. note:

An instrumental model of teacher development is limited. It attempts to capture, copy and disseminate elements of ‘good practice’, out of the context in which they were developed, in order to refresh the educational process as if retooling an industrial production line. This may appear to meet short-term needs, but does little to develop reflexive professionals capable of intelligent action in fast-changing contexts. (Fisher et al., 2006, p. 39).

Continuing Professional Development which fosters effective pedagogy and ICT within the education workforce needs to model such pedagogy in action. It needs to recognise the wider economic, social and cultural context which influences educational policy and the provision of ICT resources for learning and teaching; to reflect an informed and nuanced use of ICT as tools for learning and teaching; and acknowledge the interactive and situated nature of professional knowledge with ICT. CPD for learning professionals will model the integration of context, community and individual needs within learning communities in which professional knowledge, like intelligence, is accomplished, not possessed (Pickering et al., 2007; Pea, 1993).

References

Angeli C. and Valanides, N. (2009), Epistemological and Methodological Issues for the Conceptualization, Development, and Assessment of ICT-TPCK: Advances in Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK). Computers and Education, 52, 154-168.

Banks, F., Leach, J. and Moon, B. (1999), New Understandings of Teachers' Pedagogic Knowledge. In Leach, J. and Moon, B. (Eds.) Learners and Pedagogy. London, Paul Chapman Publishing in association with The Open University Press.

Becta (2007), Harnessing Technology Review 2007: Progress and impact of technology in education. Coventry, Becta.

Becta (2008), Harnessing Technology: Next generation learning 2008–14: A summary. Coventry, Becta.

Beetham, H. and Sharpe, R. (2007), An introduction to rethinking pedagogy for a digital age. In Beetham, H. and Sharpe, R. (Eds.) Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age: Designing and delivering e-learning. Abingdon and New York, Routledge.

Benzie, D. H. (2000), A longitudinal study of the development of information technology capability by students in an institute of higher education. Faculty of Education. Exeter, University of Exeter.

Buckingham, D. (2007), Beyond Technology: children's learning in the age of digital culture, Cambridge, Polity.

Carmichael, P. (2007), Introduction: Technological development, capacity building and knowledge construction in education research. Technology Pedagogy and Education, 16, 235-247.

Chevellard, Y. (2007), Readjusting Didactics to a Changing Epistemology. European Educational Research Journal, 6, 131-134.

Chowcat, I., Phillips, B., Poopham, J. and Jones, I. (2008), Harnessing Technology: Preliminary identification of trends affecting the use of technology for learning, Coventry, Becta.

Coleman, J. (2008), Theories of youth development: controversies of age and stage. The educational and social impact of new technologies on young people in Britain: Theorising the benefits of new technology for youth. Oxford, UK Economic and Social Research Council.

Cox, M., Webb, M., Abbott, C., Blakeley, B., Beauchamp, T. and Rhodes, V. (2003), ICT and Pedagogy. London, Department for Education and Skills.

Crook, C. (2008), Theories of formal and informal learning in the world of Web 2.0. The educational and social impact of new technologies on young people in Britain: Theorising the benefits of new technology for youth. Oxford, UK, Economic and Social Research Council.

Dale, R. (1999), Specifying globalisation effects on national policy: a focus on the mechanisms. Journal of Education Policy, 14, 1 - 18.

De Freitas, S., Oliver, M., Mee, A. and Mayes, T. (2008), The practitioner perspective on the modeling of pedagogy and practice. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 24, 26-38.

DfES (2005), Harnessing Technology: Transforming learning and children's services. London, Department for Education and Skills.

Ferdig, R. E. (2006), Assessing technologies for teaching and learning: understanding the importance of technological pedagogical content knowledge. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37, 749-760.

Fisher, T., Higgins, C. and Loveless, A. (2006), Teachers Learning with Digital Technologies: A review of research and projects. Bristol, Futurelab.

Freire, P. and Macedo, D. (1987), Literacy: Reading the Word and the World, South Hadley, Mass, Bergin and Garvey Paperback.

Gall, M. and Breeze, N. (2005), Music composition lessons: the multimodal affordances of technology. Educational Review, 57, 415 - 433.

Gardner, H. (1993), Multiple Intelligences: The theory in practice, New York, HarperCollins Publishers.

Gillen, J., Staarman, J. K., Littleton, K., Mercer, N. and Twiner, A. (2007), A learning revolution? Investigating pedagogic practice around interactive whiteboards in British primary classrooms. Learning, Media and Technology, 32, 243-256.

GTC (2006), PELRS Summary of Research Findings: The Pedagogies with E-Learning Resources Project. London, General Teaching Council for England.

Higgins, S., Beauchamp, G. and Miller, D. (2007), Reviewing the literature on interactive whiteboards. Learning, Media and Technology, 32, 213-225.

Hillocks, G. (1999), Ways of Thinking, Ways of Teaching, New York and London, Teachers College Press.

Hudson (2007), Comparing Different Traditions of Teaching and Learning: what can we learn about teaching and learning? European Educational Research Journal, 6, 135-146.

John, P. and Sutherland, R. (2004), Teaching and Learning with ICT: new technology, new pedagogy? Education, Communication and Information, 4, 101 - 107.

John, P. D. and Sutherland, R. (2005), Affordance, opportunity and the pedagogical implications of ICT. Educational Review, 57, 405-413.

Jonassen, D. H. (2006), Modelling with technology: Mindtools for conceptual change, Columbus OH, Merrill Prentice Hall.

Kennewell, S. (1995), Information technology capability - how does it develop? In Tinsley, J. D. and Van Weert, T. J. (Eds.) World Conference on Computers in Education VI: WCCE 95 Liberating the Learner. London, Chapman & Hall.

Kennewell, S. (2001), Using Affordances and Constraints to Evaluate the Use of Information and Communications Technology in Teaching and Learning. Journal of Information Technology for Teacher Education, 10, 101-116.

Klafki, W. (2000), Didaktik Analysis as the Core of Preparation of Instruction. In Westbury, I., Hopmann, S. and Riquarts, K. (Eds.) Teaching as a Reflective Practice: the German didaktik tradition. Mahwah, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P. and Yahya, K. (2007), Tracing the Development of Teacher Knowledge in a Design Seminar: Integrating Content, Pedagogy and Technology. Computers and Education, 49, 740-762.

Koskimaa, R., Lehtonen, M., Heinonen, U., Ruokamo, H., Tissari, V., Vahtivuori, H. S. and Tella, S. (2007), A Cultural Approach to Networked-Based Mobile Education. International Journal of Educational Research, 46, 11-214.

Kress, G. and Pachler, N. (2007), Thinking about the 'm' in m-learning. IN Pachler, N. (Ed.) Mobile learning: towards a research agenda. London, WLE Centre, Institute of Education.

La Velle, L. B., Wishart, J., McFarlane, A., Brawn, R. and John, P. (2007), Teaching and learning with ICT within the subject culture of secondary school science. Research in Science and Technological Education, 25, 339-349.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991), Situated Learning. Legitimate Peripheral Participation, Cambridge, CUP.

Leach, J. and Moon, B. (2008), The Power of Pedagogy, Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Sage.

Livingstone, S. (2008), Seminar Introduction: Setting the scene. The educational and social impact of new technologies on young people in Britain: Theorising the benefits of new technology for youth. Oxford, UK, Economic and Social Research Council.

Loveless, A. (2003), The interaction between primary teachers’ perceptions of ICT and their pedagogy. Education and Information Technologies, 8, 313-326.

Loveless, A. (2007), Preparing to teach with ICT: subject knowledge, Didaktik and improvisation. The Curriculum Journal, 18.

Loveless, A., Denning, T., Fisher, T. and Higgins, C. (2008), Create-A-Scape: Mediascapes and curriculum integration. Education and Information Technologies, 13, 345 - 355.

Luckin, R. (2008), The learner centric ecology of resources: A framework for using technology to scaffold learning. Computers and Education, 50, 449- 462.

Mayes, T. and De Freitas, S. (2007), Learning and e-learning: the role of theory. In Beetham, H. and Sharp, R. (Eds.) Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age: Designing and delivering e-learning. Abingdon and New York, Routledge.

Morgan, J. and Williamson, B. (2008), Enquiring Minds: Schools, Knowledge and Educational Change. Bristol, Futurelab.

Naismith, L., Lonsdale, P., Vavoula, G. and Sharples, M. (2004), Literature Review in Mobile Technologies and Learning. Bristol, Futurelab.

Pea, R. D. (1993), Practices of distributed intelligence and designs for education. In Salomon, G. (Ed.) Distributed cognitions: psychological and educational considerations. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Pearson, M. and Somekh, B. (2006), Learning Transformation with technology: a question of socio-cultural contexts. Qualitative Studies in Education, 19, 519-539.

Perkins, D. (1993), Person-plus: a distributed view of thinking and learning. In Salomon, G. (Ed.) Distributed cognitions: Psychological and educational considerations. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Pickering, J., Daly, C. and Pachler, N. (Eds.) (2007), New Designs for Teachers' Professional Learning, London, Institute of Education, University of London.

Ravenscroft, A. (2009), Social software, Web 2.0 and learning: status and implications of an evolving paradigm. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 25, 1 - 5.

Ravenscroft, A. and COOK, J. (2007), New horizons in learning design. In Beetham, H. and Sharpe, R. (Eds.) Rethinking Pedagogy afor a Digital Age: Designing and delivering e-learning. Abingdon and New York, Routledge.

Roschelle, J., Sharples, M. and Chan, T. W. (2005), Introduction to the special issue on wireless and mobile technologies in education. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 21, 159-161.

Salomon, G. (1993), Distributed cognitions – psychological and educational considerations, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Sefton-Green, J. (2006), Youth, technology and media cultures. Review of Research in Education, 30, 279-306.

Selwyn, N. (2008), From state-of-the-art to state-of-the-actual? Introduction to a special issue. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 17, 83-88.

Shulman, L. S. (1987), Knowledge and Teaching: Foundations of the New Reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57, 1-22.

Shulman, L. S. and Shulman, J. H. (2004), How and what teachers learn: a shifting perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36, 257-271.

Somekh, B. (2007), Pedagogy and learning with ICT: researching the art of innovation, London and New York, Routledge.

Stevenson, I. (2008), Tool, Tutor, Environment or Resource: Exploring Metaphors for Digital Technology and Pedagogy Using Activity Theory. Computers and Education, 51, 836-853.

Turvey, K. (2008), Student teachers go online; the need for a focus on human agency and pedagogy in learning about e-learning in initial teacher education (ITE). Education and Information Technologies, 13, 317-327.

Watkins, C. and Mortimore, P. (1999), Pedagogy: What do we know? In Mortimore, P. (Ed.) Understanding Pedagogy and its impact on learning. London, Paul Chapman Publishing.

Watson, G. (2001), Models of Information Technology Teacher Professional Development that Engage With Teachers' Hearts and Minds. Journal of Information Technology for Teacher Education, 10, 179 - 190.

Wenger, E. (1998), Communities of Practice: Learning, meaning and identity, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Wertsch, J. V. (1998), Mind as Action, New York, Oxford University Press.

Woollard, J. (2005), The implications of the pedagogic metaphor for teacher education in computing. Technology, 14, 189-204.