Category:Collaboration

Group Talk - why?

Summary of research

A useful review of research in this area is contained in Effective teaching: a review of the literature, by David Reynolds and Daniel Muijs, some of which is included here.

It is important to acknowledge that there is firm evidence that cooperative group work is effective in improving attainment compared with pupils working alone (Johnson and Johnson 1999).

Some basics

Collaborative work in small groups is designed to develop ‘higher order’ skills. The key elements are the talking and associated thinking that take place between group members. However, putting pupils in groups is no guarantee that they work as groups (Bennett 1976), so much deliberate work needs to be done to make group work productive.

According to Johnson and Johnson (1999) the cooperative group has five defining elements:

- positive independence – pupils need to feel that their success depends on whether they work together or not (they sink or swim together);

- face-to-face supportive interaction – pupils need to be active in helping one another learn and provide positive feedback;

- individual and group accountability – everyone has to feel that they contribute to achieving the group goals;

- interpersonal and small-group skills – communication, trust, leadership, decision making and conflict resolution;

- group processing – the group reflecting on its performance and functioning and on how to improve.

Collaborative small-group work

An alternative approach to individual practice is the use of cooperative small-group work during the review and practice part of the lesson. This method has gained in popularity in recent years, and has attracted a lot of research interest in a number of countries, such as the United States (Slavin 1996). In other countries such as the United Kingdom this method is still underused, however. In a recent study in primary schools Muijs and Reynolds (2001) found that less than 10% of lesson time was spent doing group work.

The use of small-group work is posited to have a number of advantages over individual practice. The main benefit of small-group work seems to lie in the co- operative aspects it can help foster. One advantage of this lies in the contribution this method can make to the development of students’ social skills. Working with other students may help them to develop their empathetic abilities, by allowing them to see others’ viewpoints, which can help them to realise that everyone has strengths and weaknesses. Trying to find a solution to a problem in a group also develops skills such as the need to accommodate others’ views.

Students can also provide each other with scaffolding in the same way the teacher can during questioning. The total knowledge available in a group is likely to be larger than that available to individual students, which can enable more powerful problem solving and can therefore allow the teacher to give students more difficult problems than s/he could give to individual students.

The main elements of collaborative group work identified as crucial by research are:

Giving and receiving help One of the main advantages of cooperative small-group work lies in the help students give one another. Not all kinds of help are necessarily useful, however. Just giving the right answer is not associated with enhanced understanding or achievement. In his review of research, Webb (1991) reports a positive relationship between giving content-related help and achievement. Giving non-content-related help did not seem to improve student achievement, though. Receiving explanations was found to be positive in some studies, and non-significant in others, this presumably because the receiver has to understand the help given and be able to use it. This may well require training the students to give clear help. Receiving non- explanatory help (e.g. being told the answer without being told how to work it out) was negatively or non-significantly related to achievement in the studies reviewed, while being engaged in off-task activities (e.g. socialising) was negative. In a more recent study Nattiv (1994) found that giving and receiving explanations was positively related to achievement, giving and receiving other help was slightly positively related to achievement, while receiving no help after requesting it was negatively related to achievement.

Necessary student social skills Effective small-group work does require a significant amount of preparation, and a number of preconditions have to be met beforehand in order for it to be effective. Firstly, students must be able to cooperate with one another, and to provide each other with help in a constructive way. A number of studies have found that while small-group work is positively related to achievement when group interaction is respectful and inclusive, use of group work is actually negatively related to achievement if group interaction is disrespectful or unequal (Linn and Burbules 1994; Battistich et al. 1993). This is very possible, as many (especially young students and students from highly disadvantaged backgrounds) have been found to lack the social skills necessary to interact positively with peers.

Thus, students often lack sharing skills, which means that they have difficulty sharing time and materials and can try to dominate the group. This problem can be alleviated by teaching sharing skills, for example by using the Round Robin technique in which the teacher asks a question and introduces an idea that has many possible answers. During Round Robin questioning a first student is asked to give an answer, and then passes his turn to the next student. This goes on until all students have had a chance to contribute.

Other students may lack participation skills. This means that they find it difficult to participate in group work because they are shy or uncooperative. This can be alleviated by structuring the task so that these students have to play a particular role in the group or by giving all students ‘time tokens’, worth a specified amount of ‘talk time’. Students have to give up a token to a monitor whenever they have used up their talk time, after which they are not allowed to say anything further. In this way all students get a chance to contribute.

Students may also lack communication skills. This means that they are not able to effectively communicate their ideas to others, obviously making it difficult for them to function in a cooperative group. Communication skills, such as paraphrasing, may need to be explicitly taught to students before small-group work can be used.

Finally, some students may lack listening skills. This can frequently be a problem with younger students who will sit waiting their turn to contribute without listening to other students. This can be counteracted by making students paraphrase what the student who has contributed before them has said before allowing them to contribute.

Organising small-group work For small-group work to be effective, one needs to take a number of elements into account in the structuring of the task. Before commencing the task, the goals of the activity need to be clearly stated and the activity needs to be explained in such a way that no ambiguity can exist about the desired outcomes of the task. The teacher needs to make clear that cooperation between students in the group is desired. According to Slavin (1996) the goals need to be group goals, in order to facilitate cooperation, which need to be accompanied by individual accountability for work done in order to avoid free-rider effects. Giving both group and individual grades can help accomplish this, as can use of a shared manipulative or tool such as a computer.

Avoiding free-rider effects can be aided by structuring the group task in such a way that every group member is assigned a particular task. One way of doing this is by making completion of one part of the task dependent on completion of a previous stage, so students will pressure each other to put the effort in to complete the stage before them. Johnson and Johnson (1994) suggest a number of roles that can be assigned to students in small groups, such as:

- the summariser, who will prepare the group’s presentation to the class and summarise conclusions reached to see if the rest of the group agrees;

- the researcher, who collects background information and looks up any additional information that is needed to complete the task;

- the checker, who checks that the facts that the group will use are indeed correct and will stand up to scrutiny from the teacher or other groups;

- the runner, who tries to find the resources needed to complete the task, such as equipment and dictionaries;

- the observer/troubleshooter, who takes notes and records group processes.

These may be used during the debriefing following the group work;

- the recorder, who writes down the major output of the group, and synthesises the work of the other group members.

After finishing the group task the results need to be presented to the whole class and a debriefing focusing on the process of the group work (the effectiveness of the collaborative effort) should be held. A useful way of starting a debriefing session is by asking students what they thought had gone particularly well or badly during group work (the observers mentioned above should be able to do this).

Research has shown that cooperative groups should be somewhat, but not too, heterogeneous with respect to student ability. Groups composed of high and medium, or medium and low, ability students gave and received more explanations than students in high-medium-low ability groups. Less heterogeneous groupings were especially advantageous for medium-ability students. When students of the same ability are grouped together, it has been found that high-ability students thought it unnecessary to help one another while low-ability students were less able to do so (Webb 1991; Askew and Wiliam 1995).

In this unit we have treated collaborative small-group work as a potential alternative to individual practice. However, many educators consider small-group work to be so advantageous that they have advocated structuring the whole lesson around the cooperative small-group work (e.g. Slavin 1996).

Extracts from Effective teaching: a review of the literature © Dr David Reynolds and Dr Daniel Muijs. Used with permission (The resource referred to here is now archived in the National Archives, and OGL licenced).

References

- Askew, M. and Wiliam, D. (1995) Recent research in mathematics education'5–16. Office for Standards in Education. ISBN: 0113500491.

- Battistich, V., Solomon, D. and Delucchi, K. (1993) ‘Interaction processes and student outcomes in cooperative learning groups’. Elementary School Journal94, 19–32.

- Bennett, N. (1976) Teaching styles and pupil progress. Open Books. ISBN: 0674870956.

- Dawes, L., Mercer, N. and Wegerif, R. (2000) Thinking together. Questions Publishing Company. ISBN: 1841900354.

- Johnson, D. W. and Johnson, R. T. (1994) Joining together: group theory and group skills. Prentice Hall. ISBN: 0205158463.

- Johnson, D. W. and Johnson, R. T. (1999) Learning together and alone: cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning. Allyn and Bacon. ISBN: 0205287719.

- Kagan, S. (1997) Cooperative learning. Kagan Cooperative. ISBN: 1879097109.

- Linn, M. C. and Burbules, N. C. (1994) ‘Construction of knowledge and group learning’. In K. Tobin (ed) The practice of constructivism in science education. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN: 0805818782.

- Lou, Y., Abrami, P. C., Spence, J. C., Paulsen, C., Chambers, B. and d’Apollonio, S. (1996) ‘Within-class grouping: a meta-analysis’. Review of Educational Research 66, 423–458.

- Mercer, N., Wegerif, R. and Dawes, L. (1999) ‘Children’s talk and the development of reasoning in the classroom’. British Educational Research Journal 25, 95–111.

- Muijs, D. and Reynolds, D. (2001) Effective teaching: evidence and practice. Sage (Paul Chapman). ISBN: 0761968814.

- National Curriculum Council and the National Oracy Project (1997) Teaching Talking and learning in Key Stage 3. National Curriculum Council titles. ISBN: 1872676278.

- Nattiv, A. (1994) ‘Helping behaviours and math achievement gain of students using cooperative learning’. Elementary School Journal 94, 285–297.

- Palincsar, A. S. and Brown, A. L. (1985) ‘Reciprocal teaching of comprehension fostering and comprehension monitoring activities’. Cognition and Instruction 1, 117–175.

- Slavin, R. E. (1991) Student team learning: a practical guide to cooperative learning. National Education Association. ISBN: 0810618451.

- Slavin, R. E. (1996) Education for all. Swets and Zeitlinger. ISBN: 9026514735.

- Webb, N. M. (1991) ‘Task-related verbal interaction and mathematics learning in small groups’. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 22, 366–389.

- This resource is part of the DfES resource "Pedagogy and practice: Teaching and learning in secondary schools" (ref: 0423-2004G) which can be downloaded from the National Archives http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110809101133/nsonline.org.uk/node/97131 The whole resource (512 pages) can be downloaded as a pdf File:Pedagogy and Practice DfES.pdf

- The resource booklets, and many 'harvested' documents are available to download, generally in editable formats from the ORBIT resources, see Category:DfE.

- The videos from the accompanying DVDs are available: Video/Pedpack1 and Video/Pedpack2

The Importance of Group Work

Summary of research

A useful review of research in this area is contained in Effective teaching: a review of the literature, by David Reynolds and Daniel Muijs, some of which is included here.

It is important to acknowledge that there is firm evidence that cooperative group work is effective in improving attainment compared with pupils working alone (Johnson and Johnson 1999).

Some basics

Collaborative work in small groups is designed to develop ‘higher order’ skills. The key elements are the talking and associated thinking that take place between group members. However, putting pupils in groups is no guarantee that they work as groups (Bennett 1976), so much deliberate work needs to be done to make group work productive.

According to Johnson and Johnson (1999) the cooperative group has five defining elements:

- positive independence – pupils need to feel that their success depends on whether they work together or not (they sink or swim together);

- face-to-face supportive interaction – pupils need to be active in helping one another learn and provide positive feedback;

- individual and group accountability – everyone has to feel that they contribute to achieving the group goals;

- interpersonal and small-group skills – communication, trust, leadership, decision making and conflict resolution;

- group processing – the group reflecting on its performance and functioning and on how to improve.

Collaborative small-group work

An alternative approach to individual practice is the use of cooperative small-group work during the review and practice part of the lesson. This method has gained in popularity in recent years, and has attracted a lot of research interest in a number of countries, such as the United States (Slavin 1996). In other countries such as the United Kingdom this method is still underused, however. In a recent study in primary schools Muijs and Reynolds (2001) found that less than 10% of lesson time was spent doing group work.

The use of small-group work is posited to have a number of advantages over individual practice. The main benefit of small-group work seems to lie in the co- operative aspects it can help foster. One advantage of this lies in the contribution this method can make to the development of students’ social skills. Working with other students may help them to develop their empathetic abilities, by allowing them to see others’ viewpoints, which can help them to realise that everyone has strengths and weaknesses. Trying to find a solution to a problem in a group also develops skills such as the need to accommodate others’ views.

Students can also provide each other with scaffolding in the same way the teacher can during questioning. The total knowledge available in a group is likely to be larger than that available to individual students, which can enable more powerful problem solving and can therefore allow the teacher to give students more difficult problems than s/he could give to individual students.

The main elements of collaborative group work identified as crucial by research are:

Giving and receiving help One of the main advantages of cooperative small-group work lies in the help students give one another. Not all kinds of help are necessarily useful, however. Just giving the right answer is not associated with enhanced understanding or achievement. In his review of research, Webb (1991) reports a positive relationship between giving content-related help and achievement. Giving non-content-related help did not seem to improve student achievement, though. Receiving explanations was found to be positive in some studies, and non-significant in others, this presumably because the receiver has to understand the help given and be able to use it. This may well require training the students to give clear help. Receiving non- explanatory help (e.g. being told the answer without being told how to work it out) was negatively or non-significantly related to achievement in the studies reviewed, while being engaged in off-task activities (e.g. socialising) was negative. In a more recent study Nattiv (1994) found that giving and receiving explanations was positively related to achievement, giving and receiving other help was slightly positively related to achievement, while receiving no help after requesting it was negatively related to achievement.

Necessary student social skills Effective small-group work does require a significant amount of preparation, and a number of preconditions have to be met beforehand in order for it to be effective. Firstly, students must be able to cooperate with one another, and to provide each other with help in a constructive way. A number of studies have found that while small-group work is positively related to achievement when group interaction is respectful and inclusive, use of group work is actually negatively related to achievement if group interaction is disrespectful or unequal (Linn and Burbules 1994; Battistich et al. 1993). This is very possible, as many (especially young students and students from highly disadvantaged backgrounds) have been found to lack the social skills necessary to interact positively with peers.

Thus, students often lack sharing skills, which means that they have difficulty sharing time and materials and can try to dominate the group. This problem can be alleviated by teaching sharing skills, for example by using the Round Robin technique in which the teacher asks a question and introduces an idea that has many possible answers. During Round Robin questioning a first student is asked to give an answer, and then passes his turn to the next student. This goes on until all students have had a chance to contribute.

Other students may lack participation skills. This means that they find it difficult to participate in group work because they are shy or uncooperative. This can be alleviated by structuring the task so that these students have to play a particular role in the group or by giving all students ‘time tokens’, worth a specified amount of ‘talk time’. Students have to give up a token to a monitor whenever they have used up their talk time, after which they are not allowed to say anything further. In this way all students get a chance to contribute.

Students may also lack communication skills. This means that they are not able to effectively communicate their ideas to others, obviously making it difficult for them to function in a cooperative group. Communication skills, such as paraphrasing, may need to be explicitly taught to students before small-group work can be used.

Finally, some students may lack listening skills. This can frequently be a problem with younger students who will sit waiting their turn to contribute without listening to other students. This can be counteracted by making students paraphrase what the student who has contributed before them has said before allowing them to contribute.

Organising small-group work For small-group work to be effective, one needs to take a number of elements into account in the structuring of the task. Before commencing the task, the goals of the activity need to be clearly stated and the activity needs to be explained in such a way that no ambiguity can exist about the desired outcomes of the task. The teacher needs to make clear that cooperation between students in the group is desired. According to Slavin (1996) the goals need to be group goals, in order to facilitate cooperation, which need to be accompanied by individual accountability for work done in order to avoid free-rider effects. Giving both group and individual grades can help accomplish this, as can use of a shared manipulative or tool such as a computer.

Avoiding free-rider effects can be aided by structuring the group task in such a way that every group member is assigned a particular task. One way of doing this is by making completion of one part of the task dependent on completion of a previous stage, so students will pressure each other to put the effort in to complete the stage before them. Johnson and Johnson (1994) suggest a number of roles that can be assigned to students in small groups, such as:

- the summariser, who will prepare the group’s presentation to the class and summarise conclusions reached to see if the rest of the group agrees;

- the researcher, who collects background information and looks up any additional information that is needed to complete the task;

- the checker, who checks that the facts that the group will use are indeed correct and will stand up to scrutiny from the teacher or other groups;

- the runner, who tries to find the resources needed to complete the task, such as equipment and dictionaries;

- the observer/troubleshooter, who takes notes and records group processes.

These may be used during the debriefing following the group work;

- the recorder, who writes down the major output of the group, and synthesises the work of the other group members.

After finishing the group task the results need to be presented to the whole class and a debriefing focusing on the process of the group work (the effectiveness of the collaborative effort) should be held. A useful way of starting a debriefing session is by asking students what they thought had gone particularly well or badly during group work (the observers mentioned above should be able to do this).

Research has shown that cooperative groups should be somewhat, but not too, heterogeneous with respect to student ability. Groups composed of high and medium, or medium and low, ability students gave and received more explanations than students in high-medium-low ability groups. Less heterogeneous groupings were especially advantageous for medium-ability students. When students of the same ability are grouped together, it has been found that high-ability students thought it unnecessary to help one another while low-ability students were less able to do so (Webb 1991; Askew and Wiliam 1995).

In this unit we have treated collaborative small-group work as a potential alternative to individual practice. However, many educators consider small-group work to be so advantageous that they have advocated structuring the whole lesson around the cooperative small-group work (e.g. Slavin 1996).

Extracts from Effective teaching: a review of the literature © Dr David Reynolds and Dr Daniel Muijs. Used with permission (The resource referred to here is now archived in the National Archives, and OGL licenced).

References

- Askew, M. and Wiliam, D. (1995) Recent research in mathematics education'5–16. Office for Standards in Education. ISBN: 0113500491.

- Battistich, V., Solomon, D. and Delucchi, K. (1993) ‘Interaction processes and student outcomes in cooperative learning groups’. Elementary School Journal94, 19–32.

- Bennett, N. (1976) Teaching styles and pupil progress. Open Books. ISBN: 0674870956.

- Dawes, L., Mercer, N. and Wegerif, R. (2000) Thinking together. Questions Publishing Company. ISBN: 1841900354.

- Johnson, D. W. and Johnson, R. T. (1994) Joining together: group theory and group skills. Prentice Hall. ISBN: 0205158463.

- Johnson, D. W. and Johnson, R. T. (1999) Learning together and alone: cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning. Allyn and Bacon. ISBN: 0205287719.

- Kagan, S. (1997) Cooperative learning. Kagan Cooperative. ISBN: 1879097109.

- Linn, M. C. and Burbules, N. C. (1994) ‘Construction of knowledge and group learning’. In K. Tobin (ed) The practice of constructivism in science education. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN: 0805818782.

- Lou, Y., Abrami, P. C., Spence, J. C., Paulsen, C., Chambers, B. and d’Apollonio, S. (1996) ‘Within-class grouping: a meta-analysis’. Review of Educational Research 66, 423–458.

- Mercer, N., Wegerif, R. and Dawes, L. (1999) ‘Children’s talk and the development of reasoning in the classroom’. British Educational Research Journal 25, 95–111.

- Muijs, D. and Reynolds, D. (2001) Effective teaching: evidence and practice. Sage (Paul Chapman). ISBN: 0761968814.

- National Curriculum Council and the National Oracy Project (1997) Teaching Talking and learning in Key Stage 3. National Curriculum Council titles. ISBN: 1872676278.

- Nattiv, A. (1994) ‘Helping behaviours and math achievement gain of students using cooperative learning’. Elementary School Journal 94, 285–297.

- Palincsar, A. S. and Brown, A. L. (1985) ‘Reciprocal teaching of comprehension fostering and comprehension monitoring activities’. Cognition and Instruction 1, 117–175.

- Slavin, R. E. (1991) Student team learning: a practical guide to cooperative learning. National Education Association. ISBN: 0810618451.

- Slavin, R. E. (1996) Education for all. Swets and Zeitlinger. ISBN: 9026514735.

- Webb, N. M. (1991) ‘Task-related verbal interaction and mathematics learning in small groups’. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 22, 366–389.

- This resource is part of the DfES resource "Pedagogy and practice: Teaching and learning in secondary schools" (ref: 0423-2004G) which can be downloaded from the National Archives http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110809101133/nsonline.org.uk/node/97131 The whole resource (512 pages) can be downloaded as a pdf File:Pedagogy and Practice DfES.pdf

- The resource booklets, and many 'harvested' documents are available to download, generally in editable formats from the ORBIT resources, see Category:DfE.

- The videos from the accompanying DVDs are available: Video/Pedpack1 and Video/Pedpack2

Speaking and Listening in Group Work

This resource is licenced under an Open Government Licence (OGL).

This resource is an adapted version of an Initial Teacher Education - English resource, the original of which is available at: http://www.ite.org.uk/ite_topics/speaking_listening_reception/001.html

Speaking and Listening at Reception and Key Stage 1

| Jennifer Logue

Senior Lecturer Department of Childhood and Primary Studies University of Strathclyde |

1 Introduction

Developing Speaking and Listening at Reception and Key Stage 1 will involve children in a range of experiences some of which may be incidental and occur as part of ongoing involvement in play. However, such is the potential of group talk in supporting learning that it cannot always be left to chance. As well as encouraging students to engender an enabling classroom ethos for talk, they will need support in planning opportunities for children to collaborate to construct meaning together.

In teaching students about speaking and listening it is important to mirror good classroom practice in this area. Students are therefore encouraged to collaborate in small groups to explore issues and deepen their learning. The web pages focus on supporting students in forming groups and devising tasks for talk as these are problematic areas for students in the development of speaking and listening. These are also aspects which are often unplanned for resulting in learning being inhibited rather than promoted Blatchford & Kutnick (2003).

2 Forming Groups

Often students are keen to implement group talk activities in the classroom but are unsure about how to group children for these activities. We are keen that group talk takes place as a way of learning in all areas of the curriculum and this can present further uncertainty as children may already be grouped in attainment groups, social groups etc. It is especially important that this is explored with students as the success of group talk is contingent upon group size and composition

2 Forming Groups

2.1 Group Size

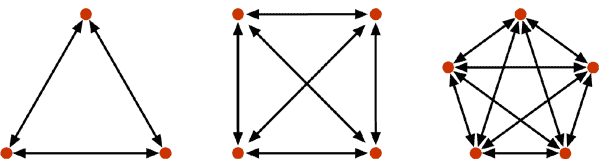

Before any examination of how to group children for talk activities, it is essential to consider with students the optimum number of children who can usefully talk in each group. Faced with classes where children may be seated in groups of 6, 8, 10, students may be tempted to set up group talk for groups of similar numbers. Guidance is fairly clear that groups of four allow for a range of ideas without the lines of communication becoming too complicated. Figure 6.3 in Bennett & Dunne (1994) is useful in exemplifying the lines of communication in groups of 3 to 5 children. See below.

There is also advice maintaining that pairs can work well together as it is difficult not to respond to one other person and this is well worth students considering for children at Foundation stage and KS1.

2 Forming Groups

2.2 Group Composition

2.2.1 Criteria for Forming Groups

A useful starting point in exploring how groups of four might be established is in asking groups of students to select and rank six criteria for forming groups from the possibilities listed below, adding any others they might think of.

- Ability to write

- Ability to Read

- Friendship

- Imagination

- Ability to Listen

- General Knowledge

Students are then asked to work on their own to read the quotes below related to forming groups. They should then regroup to review their selection and ranking of criteria for forming groups in light of their reading. The suggestion would be that no matter whether children were grouped in attainment groups in, e.g. Mathematics or mixed attainment groups in, e.g. Science, personality is central to decision making when forming groups. Further to this, it is likely that more effective collaboration will be experienced in groups where similar personalities are grouped together. This idea can often take students by surprise as they initially regard mixing personalities as a ‘fairer’ way of organising groups.

Personality …reluctant or hesitant speakers may feel able to participate when their more confident peers are absent, whereas dominant pupils put together may benefit from learning to cope with the contribution of those with similar traits. Holderness & Lalljee (1998)

…extrovert personalities are more likely to interact in small groups and introverts are less likely to interact.Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

Gender Tann’s (1991) experimental structuring of collaborative tasks used mixed-gender groups and found boys to be argumentative in discussion, while girls tried to reach agreement in a more consensual manner. Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

She (Webb 1991) found that an imbalance in number of boys and girls leads to gender differences similar to those found by Tann, but recommends equal numbers of boys and girls in each group to achieve balance in discussion and successful problem solving.Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

Girls will often participate more freely in a technology or science task without the presence of boys. Holderness & Lalljee (1998)

Friendship Friendship, thus, may limit achievement in problem-solving tasks and general development of co-operative skills in the classroom. Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

…groups of close friends may take so much for granted about each other that they are not able to talk in an exploratory or open way, or to be explicit about their thinking with each other- they may tend to leave much unsaid. Howe (1997)

Friends tend to agree with one another on principle, and less confident children make no contribution at all, to avoid being held responsible later on. Grugeon, Hubbard, Smith & Dawes (1998)

Attainment Groups function best when they are of mixed ability but such groups must include pupils from the highest ability groups within the class. Galton & Williamson (1992)

Homogeneous high-ability groups do not display high-level elaborative interactions when asked to jointly solve a problem; most pupils want to work as individuals. Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

Homogeneous low-ability groups have little stimulus (from more knowledgeable group members) for high-order elaborative interactions and much of their interaction is off task. Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

Webb’s evidence concerning heterogeneous/mixed ability groups finds that these groups were more likely to use high elaborative interactions leading to problem solving achievement. Kutnick & Rogers (1994)

Bilingualism There may be times when a bilingual group will enable pupils to use a shared home language, providing mutual support, while at other times a mixed language group may provide a necessary stimulus. Holderness & Lalljee (1998)

2 Forming Groups

2.2 Group Composition

2.2.2 Planning for group size and composition

To pull the aspects of group size and composition together, the following scenario can be given to groups of students to consider, having firstly given time for individuals to think about it on their own. As part of their deliberations, students should be guided to read differing views on the advantages and disadvantages of appointing a group leader.

Scenario Ms Borland thinks that the History curriculum provides a useful context for the development of speaking and listening. She has therefore begun to incorporate more group talk activities into her topics. She has noticed in one of the groups that out of 6 children only three participate to any great extent. She has decided that she will appoint a group leader in the hope that it will encourage wider participation.

- Why might a limited number of children be participating in the talking tasks?

- To what extent do you think her idea about appointing a group leader will encourage greater participation?

- What other options could the teacher consider to increase participation?

3 Structuring Tasks Within A Curricular Context

Introduction

The pressure in schools for balance and breadth and the higher profile of other forms of language can mean that some teachers allocate infrequent, isolated periods of time for group talk, or worse, relegate it to the ‘it would be nice to do it if only I had the time’ agenda. It is important that students see the potential for group talk as a means of learning in all curricular areas rather than a rarely timetabled part of the Language curriculum alone. 3.1 The potential of group talk

To help to convince students of the power of group talk in children’s learning, it is useful to have them view a video clip or examine a transcript of children talking. The transcript included below from Grugeon et al (2005) can be used for this, or, indeed, any other extract where children are grappling with meaning in a purposeful task. Students should be issued with the transcript and asked in pairs to consider how children are helping one another to make meaning. Students should also be provided with the accompanying table as a starting point to help them analyse the children’s talk.

Transcript: Three children in a lower school, 7 and 6 years old, discuss snails in a snailery, without their teacher present

| Susan: | Yes, look at this one, it's come ever so far. This one's stopped for a little rest ... |

| Jason: | It's going again! |

| Susan: | Mmmm good! |

| Emma: | This one's smoothing ... slowly |

| Jason: | Look, they've bumped into each other (laughter) |

| Emma: | It's sort of like got four antlers |

| Susan: | Where? |

| Emma: | Look! I can see their eyes |

| Susan: | Well, they're not exactly eyes ... they're a second load of feelers really aren't they? No . . . and they grow bigger you know ... and at first you couldn't hardly see the feelers and then they start to grow bigger, look |

| Emma: | Look ... look at this one he's really come ... out ... now |

| Jason: | It's got water on it when they move |

| Susan: | Yes, they make a trail, no let him move and we see the trail afterwards ... |

| Emma: | I think it's oil from the skin |

| Jason: | Mmm ... it's probably moisture ... See, he's making a little trail where he's been ... they ... walk very ... slowly |

| Susan: | Yes, Jason, this one's doing the same, that's why they say slow as a snail |

| Emma: | Ooh look, see if it can move the pot ... |

| Jason: | Doesn't seem to |

| Susan: | Doesn't like it in the p… when it moves in the pot ... look, get him out! |

| Jason: | Don't you dare pull its shell off |

| Emma: | You'll pull its thing off shell off … ooh it's horrible! |

| Jason: | Oh look ... all this water! |

Analysing the children’s talk

| Collaborative Meaning Making | Examples from Extract |

|---|---|

| Questioning | |

| Disagreeing | |

| Extending | |

| Qualifying | |

| Changing Views | |

| Revisiting Ideas |

Adapted from: p.7 Handbook, DfES (2003) Speaking, Listening, Learning: working with children in Key Stages 1 and 2, Primary National Strategy.

3.2 Identifying talking tasks across the curriculum

While there are useful techniques which will help students structure good talking tasks for children, and which will be considered subsequently, undertaking the following activity can de-mystify the notion of what talking tasks look like in different curricular areas. This is particularly important when students are placed in classes where individual written tasks predominate and there are few opportunities to experience children working on talking tasks across the curriculum.

It can be helpful, initially, for students to identify opportunities for talk under two broad headings: presentational talk and exploratory talk. Students should be aware that presentational talk tends to occur when the child is speaking to an ‘audience’, offering their ideas for display and evaluation. This type of talk is often more polished and complete. Exploratory talk helps children work on their understanding by allowing them to hear how their ideas sound and letting them modify their ideas in response to others.

Students should be provided with a copy of the table below and asked to work in groups to identify the type of talk which is likely to be the main focus of each of the tasks. They should then consider in which curricular area each of the talking tasks might be undertaken.

Examining Talking Tasks

| Talking tasks | ||

| Explaining how to make a wax resist painting | ||

| Using a plan to select suitable locations for the litter bins in the playground | ||

| Choosing a verse for a new baby card | ||

| Describing the visit to the fire station | ||

| Reporting the results of a floating/sinking experiment | ||

| Devising a true/false shape quiz | ||

| Recommending a book for a 5 year olds birthday | ||

| Planning a survey about items to sell in the tuck shop |

| Type | Curricular Areas |

| Presentational Talk (P) Exploratory Talk (E) |

# Language

|

3.3 Features of effective talking tasks

Many students find it difficult to plan effective group talk tasks. This is perhaps not surprising given what has been suggested earlier about the dearth of such tasks in many classrooms. To support students with their planning it is important to identify what the features of a good talking task are. That is to say, tasks with which children stay engaged, the talk is task related and children’ thinking is developed. This process can be started by asking groups to compare two tasks to derive what makes one task more likely to maintain involvement than the other. The tasks outlined below, based on Inga Moore’s book ‘Six Dinner Sid’, published by Hodder Children’s Books, should help students to do this.

Here are two tasks, Task A and Task B, which apparently cover the same content. Students should be given both tasks and asked to decide which one would be more likely to encourage children to talk in groups effectively. Hopefully, they will go for Task B! Students should now focus on Task B and identify at least 3 features which make it more effective.

Task A — Six Dinner Sid Equipment for Sid One of Sid’s owners is going to the pet shop for things she needs for Sid. Make a list of things she should buy.

Task B — Six Dinner Sid Equipment for Sid One of Sid’s owners is going to the pet shop for things she needs for Sid. There are lots of things to choose from, but Sid’s owner can’t buy them all at once.

Sort out the items into things she should buy today, things she should buy later and things she doesn’t need to buy at all.

Decide on 3 things she should buy today. Make a list of these things.

(Cut into heading for children to use for sorting)

(Using actual items or photographs / pictures of items)

Features common to both tasks

- There is a real or realistic purpose to the task

- The children have enough knowledge to talk about the topic

- The task builds on previous learning experiences

- There is a clear outcome

- The task is open enough to allow for a diversity of views (however in Task A this may lead to disputational or cumulative talk rather than exploratory talk, Grugeon, Dawes, Smith & Hubbard (2005)).

Features more specific to Task B

- The children's curiosity will be aroused

- The children need to talk to produce a satisfactory outcome

- The task resources are presented in ways which will enable children to modify opinions, add suggestions, change their minds etc. in light of the discussion

- There is a problem or dilemma; something to be worked out

3.4 Using task structures

The list of task structures below, adapted from Gavienas & Logue (2004), will help take students to the next stage in planning their own talking tasks.

Task structures

- Add to/amend/remove/select items from a given list.

- Group statement about something under given headings.

- Categorise and devise headings for statements, objects and so on.

- Prioritise statements, steps, procedures and so on.

- Note pros/cons of given features of objects, items and so on (e.g. the safety, appeal, texture, colour of babies’ toys).

- Sort statements into, e.g. agree/disagree/can’t decide or true/false.

- Give precise criteria for children to adhere to, e.g. captions have no more than six words.

- Compare two things under given headings.

- Choose from options and justify choices.

- Convert from one form to another, e.g. text to map, diagram to 3-D model, text to illustration.

- Order items, procedures, events and so on according to given or agreed criteria.

- Organise pictures, items, statements onto a continuum, e.g. most favourite - least favourite

Students should be given time to work in groups to restructure the following task using the list above.

Six Dinner Sid A Name for the New Cat One of Sid’s owners has decided to get another cat to keep Sid company. Think of a name for the new cat.

If these are displayed on large sheets of paper students can identify which task structures have been used from the 1-12 above and compare the different ways tasks have been restructured.

3.5 Analysing talking tasks

To widen students’ experience of the different forms talking tasks might take, the chapter Who’s Asking The Questions? Hunt N, & Luck C, in Use of Language Across the Curriculum Bearne E, ed. (1998) should be read and summarised in relation to the structures and groupings used by a teacher undertaking a history topic. This will also reinforce the idea that speaking and listening activities should be an integral part of the curriculum which should be regularly planned for. The grid might be useful to help students’ notetake as they read.

“Who’s Asking the Questions?”

| Talking task | ||

| 1. | ||

| 2. | ||

| 3. | ||

| 4. | ||

| 5. | ||

| 6. | ||

| 7. |

Students could usefully deepen their understanding in relation to designing group tasks by reading Bennett & Dunne (1994) chapters 4&5, Designing tasks: Cognitive aspects and Social aspects and Sue Lyle’s chapter, Sorting out learning through group talk, in Goodwin (2001).

Once students have undertaken their reading, groups could be given a range of examples of talking tasks gleaned from different sources and asked to arrange them on an effective / less effective continuum. This should generate discussion and develop understandings about when loose or tight frameworks Bennett & Dunne (1994) might be more appropriate for the stage and context children are working at.

4 Other ideas for speaking and listening

- The Scholastic series, ‘Speaking and Listening in Cross Curricular Contexts’ published in 2004, provides a wealth of ideas for talking tasks related to national curriculum topics in Geography, History and Science at KS1 & 2. Students are finding these books to be invaluable resources on school placements from Reception to Year 6.

- ‘Teaching Citizenship through Traditional Tales (2003) Ellis, S. & Grogan, D. published by Scholastic, provides opportunities for group talk through thought-provoking letters from fictional characters allowing children to explore moral issues within the safe environment of fictional tales.

- SCCC (1998) provides support for students in developing children’s speaking and listening by suggesting possible next steps in ‘Assessment in the Classroom: Listening and Talking’.

Practical Considerations

Review all the ideas you have explored relating to group work, some of which are summarised in the table below. Circle in colour any ideas you have never used or considered.

In another colour highlight the ideas you intend to try with your case study class. Of these, prioritise with numbers the idea you think will have most impact in your lessons.

Reflect on your practice after each lesson. When you have successes or difficulties with the case study class, share them with other teachers who may have ideas to help you.

After at least four weeks of putting these ideas into practice, carry out the original questionnaire again – both your own views on pupils’ likely perceptions, plus the pupils’ views themselves.

Putting it into practice

| Grouping – size and composition

I could use … |

Managing groups

|

Stimulus for group talk

|

| pairs | pair talk | explanation for group talk |

| small group (three or four) | pairs to fours | demonstration for group talk |

| large group (five to seven) | snowball | question and answer for group talk |

| friendship grouping | spokesperson | taking notes using group talk |

| ability grouping | envoys | worksheets and book exercises using group talk |

| groups with similar personalities together | rainbow groups | practical work using group talk |

| groups with different statements | number/letter/colour | misconceptions or false personalities together |

| single-sex groups | random numbering | artefacts, photographs, etc. |

| groups with equal numbers of boys/girls per group | random continuum | open ended questions |

| random selection for grouping | other ideas | group concept or mind maps |

| groups with pupils with same first language | other ideas | concept cartoons

card sorts or continuum |

| other ideas |

Summary

Whatever you choose to do, remember:

- grouping plans rather than seating plans;

- the choice of seating and grouping is yours;

- express grouping and seating in terms of learning not behaviour;

- change groups regularly;

- ensure pupils know what the purpose and the product of the discussion will be;

- make explicit the reason why they should;

- be considerate to the views of others;

- face each other, and sit as close together as possible;

- use eye contact;

- clear the desks before they talk as a group;

- work within the time targets set;

- don’t loom or lean;

- speak to them at their level or lower;

- encourage non-verbally: eyes, face and gesture;

- withhold your opinion or the ‘correct’ answer for as long as possible;

- ask questions rather than provide answers;

- use others’ answers as prompts for argument.

Pedagogical Strategies(i)

Pages in category "Collaboration"

The following 18 pages are in this category, out of 18 total.